Original Article

Hell J Surg. 2024 Jul-Sept;94(3):115–141

doi: 10.59869/24037

Greek Pelvic Exenteration Collaborative

(Author names and affiliations Appendix 1)

Correspondence: Christos Kontovounisios, 2nd Surgical Department Evaggelismos Athens General Hospital, 45-47 Ipsilantou St. 106 76 Athens, Greece, e-mail: c.kontovounisios@hotmail.com

Abstract

Background: Surgical treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) and locally recurrent rectal cancer (LRRC) relies on Pelvic Exenteration, a complex procedure with high morbidity and mortality rates and great disparities in practice across different centers internationally. The aim of this survey is to review the current perioperative management of LARC and LRRC in Greece.

Material and Methods: National Snapshot Survey disseminated online by the Hellenic Surgical Society and Greek Society of Coloproctology.

Results: Most respondents were surgeons, 22% of whom had received fellowships in pelvic exenteration surgery. 83% of the participants reported holding multidisciplinary team meetings, and typically fewer than 10 pelvic exenteration procedures are conducted annually. A total of 28% of the participants employ a validated classification system to describe the operative approach (Pelvic Exenteration Lexicon). Considering outcomes, surgical factors like length of stay (78%), ICU duration (72%), blood loss (70%) and number of blood transfusions (64%) were prioritised, whereas patient-reported outcomes focused on physical functioning (77%), quality of life (75%), and urinary function (75%). For urological reconstructions, percutaneous nephrostomy (87%), cutaneous ureterostomy (75%) and urinary diversion using an ileal conduit (73%) were utilised the most, while plastic reconstructions involved mainly mesh placement (72%), omental flap with/without a skin graft (70%) and pedicled flaps (58%). Most prevalent complications were perineal wound dehiscence, abdominal wall hernia, postoperative ileus, urinary infection and VTE.

Conclusion: Due to its complexity and low volume, experience in LARC/ LRRC is dispersed and differs among individuals. There is a need for structured, validated national guidelines to standardise methods and ensure that patients receive the highest standard of care.

Key Words: Rectal cancer, locally advanced, recurrent, pelvic exenteration

Submission: 03.08.2024, Acceptance: 06.11.2024

INTRODUCTION

In 2024, it is expected that approximately 106,590 new cases of colon cancer and 46,220 new cases of rectal cancer will be diagnosed in the United States and an estimated total of 53,010 individuals will lose their lives due to these cancers [1].

In Greece, despite the absence of a national cancer registry to furnish reliable statistics [2], there were 1,100 newly documented cases of rectal cancer in 2022, corresponding to an age-standardized incidence rate of 9.1 per 100,000 population [3].

The primary curative treatment for rectal cancer is surgical resection accompanied by Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) [5]. Although resection and TME are associated with low tumour recurrence rates, locally advanced rectal cancer (T3-4N0M0 or T1-4 N1-2M0 tumours), poses greater challenges for achieving complete or R0 resection compared to early-stage disease [6]. Undesirably, even with optimal surgery and supplementary treatments, about 10% of patients encounter a local recurrence, with roughly half of them having solely locoregional disease [7].

The surgical approach to treating LARC and locally recurrent rectal cancers (LRRC) relies on Pelvic Exenteration (PE), a procedure originally outlined by Brunschwig for cervical cancer in 1948 [8]. PE is an extensive surgical procedure aimed at removing these malignancies radically, with the aim of a negative resection margin, by partially or completely excising nearby affected pelvic structures, including rectum, bladder, uterus, fallopian tubes, vagina, as well as major pelvic blood vessels, nerves, and pelvic bones [9]. This procedure has been found to provide a five-year survival rate for LARC between 52% to 65%, and for LRRC between 35% to 50% [10]. However not all LARC/ LRRC cases are suitable for exenteration procedures; the percentage of exenteration procedures among the total referrals of patients with LARC and LRRC, between 2010 and 2014, in a multidisciplinary colorectal cancer center in the United Kingdom, was estimated to be 41% and 16%, respectively [11].

However, it results in increased morbidity and greater functional compromise. This demands specialised perioperative care and the involvement of a multidisciplinary team of health practitioners [12]. Although there has been an effort to standardise the perioperative and anaesthetic considerations in PE and recent guidelines have been published [13], there are wide disparities in practice across different centers internationally.

The purpose of this article is to present a snapshot of the current practice in Greece, related to the perioperative management of patients undergoing a PE for LARC/ LRRC.

METHODS

We conducted a cross- sectional study that focused on several important factors that rule the intraoperative management of the patients with LARC/ LRRC treated with a pelvic exenteration procedure. An online survey was structured, using the online platform of Microsoft Forms and it was sent by email to the Greek Society of Coloproctology (GSCP) and the Hellenic Surgical Society (HSS) for validation and subsequently, it was forwarded online to all their members for response. A follow-up email was forwarded after 15 and 20 days, respectively, to serve as a reminder. The results of the survey were transferred to the Microsoft Office Excel application for subsequent analysis and chart formation.

Unless stated otherwise, all percentages described below refer to the number of the responses received in the respective topic. Questions included in the survey are available at the Appendix 2.

RESULTS

We received a total of 60 replies. Except for one radiation oncologist and one medical oncologist, all other participants were surgeons, 22% of whom had undergone some form of specialised training or fellowship in Pelvic exenteration surgery. Nearly half of them (55%) have been treating patients with LARC/ LRRC for 5-20 years (Supplementary Figure 1). At our national institutions, public or private, ten or less Pelvic exenteration procedures are performed most commonly (53%), and only six participants (10%) reported higher numbers.

Pre-operative considerations

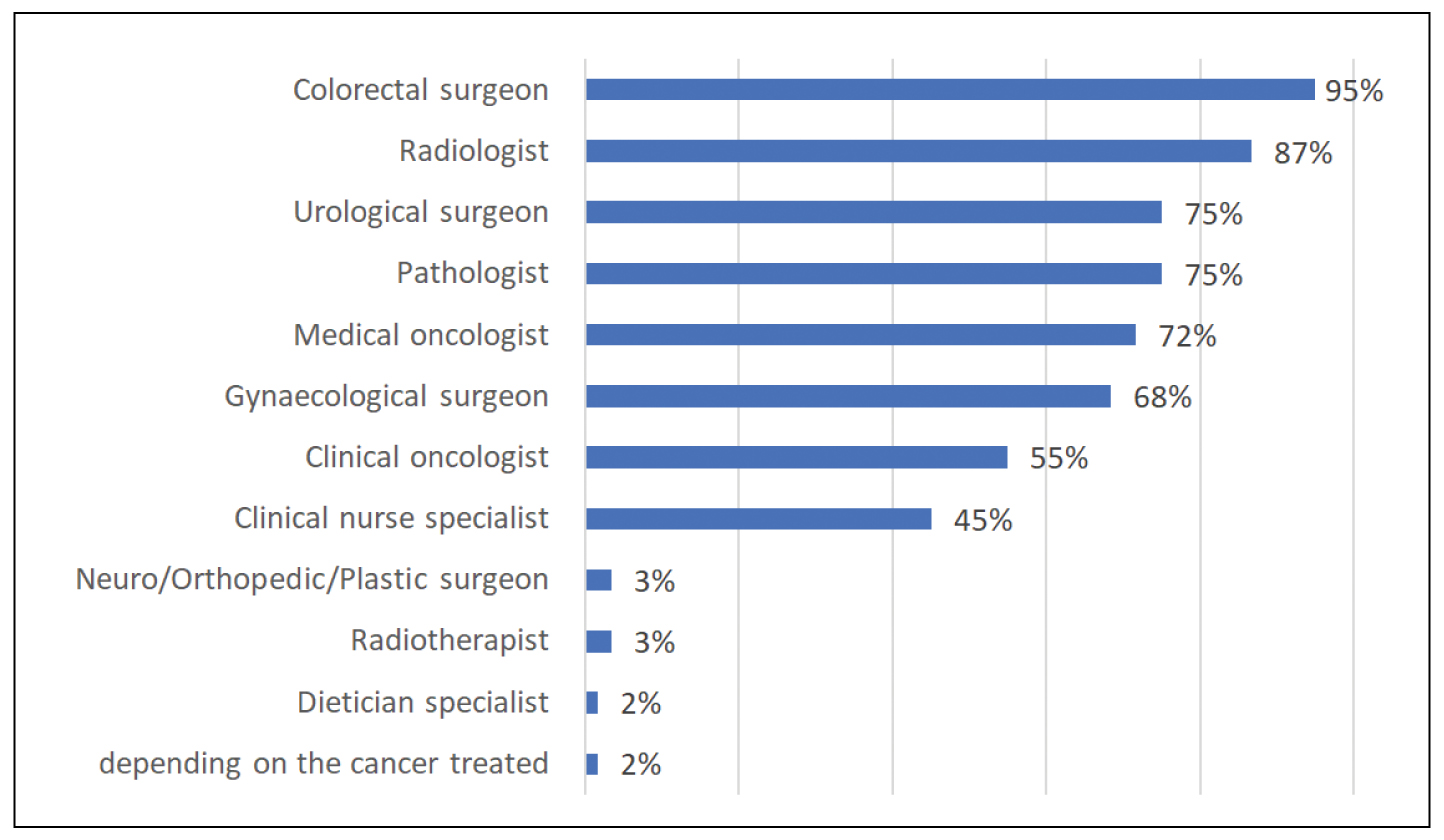

In 83 %, a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) or tumour board meeting is hosted and most participants (98%) believe that the implementation of a standardised system and template for reporting outcomes of an advanced pelvic cancer MDT should be considered. The optimal MDT handling LARC/ LRRC, according to our results, should have a designated MDT lead/chair, such as a colorectal, gynaecological or urological consultant (75%) and should be composed of many specialties, including general surgeons (95%), radiologists (86%), pathologists (75%), urologists (75%), medical and clinical oncologists (71% and 55%, respectively), gynaecologists (68%) and a clinical nurse specialist (45%). Other specialties like radiotherapists, neurosurgeons, orthopaedic and plastic surgeons and dietitians are thought to be selectively involved, depending on the case being discussed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Optimal composition of an advanced pelvic cancer multidisciplinary team.

For staging purposes, a pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is used by all (100%) participants and 52% of them also implement both a Computerised tomography (CT) scan and a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is selected by four participants (7%), always as an adjunctive to MRI for local staging (Supplementary Figure 2).

Neoadjuvant long course chemoradiotherapy and total neoadjuvant treatment are the leading forms of neoadjuvant treatment applied (75% and 72%, respectively), while short course radiotherapy and immunotherapy are reported by less than half of the participants (45% and 45%, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 3). Except classical radiotherapy, brachytherapy (28%) and cyberknife (18%) are also reported as alternative/ adjunctive radiotherapy techniques, whereas other methods like proton beam therapy, intraoperative radiofrequency ablation and intraoperative radiotherapy are used infrequently (7%, 7% and 2%, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 4).

In the pre-assessment of patients undergoing PE, 85% of participants strongly believe that all patients should be admitted on the night before surgery for intravenous fluid adjustment and optimisation. The presence of a prehabilitation program to enhance the nutritional status and preoperative fitness of patients undergoing PE is practiced by 28% of the responders. The anaesthetist conducting a PE case is unanimously (97%) suggested that should personally undertake the pre-assessment of the patient.

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET) has been found mandatory (92%) in the pre-assessment process, and in its absence, other essential components commonly reported are image stress testing (80% of the participants, 64% of whom reported its use only if metabolic equivalent of task (MET) <4), preoperative cardiac consultation (67%), resting echocardiography (45%) and spirometry (1%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Other essential components in the preoperative assessment of Pelvic Exenteration patients, if CPET is unavailable. N/A; no answer.

Intraoperative considerations

In the operation theater (OR), a specialised anaesthesiologist team, including nurses or Operating Department Practitioners (ODPs) who possess specific training for collaboration with the anaesthesiologist is perceived mandatory by 65% of participants. If the PE is expected to exceed 12 hours, engagement of an additional consultant anaesthesiologist, trainee anaesthesiologist, or both is considered wise (22%, 5% and 67%, respectively). Regarding the given form of anaesthesia, 53% of the participants believe that total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) is suitable for these cases, 5% neglect TIVA, while a significant portion (42%) refrain from expressing an opinion.

In the OR, an Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) machine is considered imperative, by most participants (75%) to be ensured, in order to minimise the need for anaesthesiologists to briefly vacate the operating theatre during Pelvic Exenteration procedures, while nearly half of them also select Thromboelastography (TEG) / clotting tests and Rapid infusers (47% and 43%, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 5).

Maintenance of a readily accessible supply of both blood products and reconstituted blood products, allowing for immediate administration upon request from an anaesthetist is considered standard of practice by most participants (90%) and transfusion of clotting products is thought vital to be guided by TEG monitoring (63%). Before commencing any case, nearly all participants (93%) cross match, group and save packed Red Blood Cells (pRBCs), with 4 units being the commonest (53%). Additionally, 48% reported saving 1 liter of Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) units and 22% 1 unit of pooled platelets (Supplementary Figure 6).

Tranexamic acid is preferred to be given intraoperatively, if required, at a dose of 1g or 500mg (42% and 23%, respectively), while its routine use immediately preoperatively is seldom practised (12%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Opinions regarding the intraoperative use of IV Tranexamic acid. N/A; no answer.

For prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE), low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) are utilised both preoperatively if the patient is admitted more than 24 hours from the time of surgery, and postoperatively (93%). The three predominantly used agents are enoxaparin (40%), Tinzaparin (28%) and Bemiparine (23%) (Supplementary Figure 7). The typical VTE prevention protocol employed (72%) is both LMWH and thromboembolic deterrent stockings (TEDs), with or without intermittent pneumatic compression devices (IPCs).

Apropos the PE procedure, a validated classification system to describe the operative approach in rectal cancer (Pelvic Exenteration Lexicon) is reported to be followed by less than one third (28%) of the participants.

Plastic reconstruction options in PE cases include most frequently mesh placement (72%), omental flap with/without a skin graft (70%) and pedicled flaps (58%) (Supplementary Figure 8). Participants who utilize flaps report that the vertical or oblique rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap is the most frequently chosen option (51%) (Figure 4). Urinary diversion techniques that are most frequently utilised are percutaneous nephrostomy (~86%), cutaneous ureterostomy (~75%) and urinary diversion using an ileal conduit (~73%) (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Flap preference (excluding the omental flap).

Figure 5. Vital equipment in order to minimise the need for anaesthesiologists to briefly vacate the operating theatre, during Pelvic Exenteration procedures. N/A; not answered.

Postoperative considerations

For postoperative pain management, there is an agreement (93%) that PE cases should comply with a careful postoperative pain management protocol that ensures continuous efficacy of regional anaesthesia. Most participants agree with routine, unless contraindicated, placement of epidural anaesthesia (85%) and with selection of tunneled epidural catheters (75%) in order to prolong analgesia up to 10 days. Besides epidural, paracetamol and IV opiated are most commonly involved (69% and 58%, respectively), while non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used less frequently (41%) (Supplementary Figure 9).

Commonest wound related complications are perineal wound dehiscence (73%) and abdominal wall hernia (55%) (Supplementary Figure 10). Postoperative ileus and bowel obstruction, urinary infection and VTE are the most frequently reported gastrointestinal (Supplementary Figure 11), urinary (Supplementary Figure 12) and vascular (Supplementary Figure 13) related complications (86%, 58% and 73%, respectively).

Following a PE procedure, most critical surgery- related outcomes seem to be length of hospital stay (78%), length of Intensive care unit (ICU) admission (72%) and total blood loss (70%) (Figure 6), while overall survival rates with the disease are considered the most vital (survival) outcome (64%). Interpreting the patient-related outcomes, physical status (77%), global quality of life (75%) and urinary function (72%) are considered the most essential factors (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Important surgery- related outcomes following Pelvic Exenteration.

Figure 7. Important patient-reported outcomes and functions following Pelvic Exenteration surgery.

Immediately postoperatively, the majority of the participants (85%) find the anticipated Systemic inflammatory reaction (SIRS) severe, which may result in haemodynamic instability and they consider imperative to transfer the patient to the ICU, ventilated and sedated, until it has subsided. The ability to predict the severity of SIRS on initial pre-assessment of the patient is debated; 40% of the participants agree, 32% disagree and 28% abstain from responding.

DISCUSSION

Effective multidisciplinary perioperative and anaesthetic management is crucial for achieving successful surgical outcomes in patients undergoing PE for LARC/ LRRC. The last few years there has been a collective effort through PELVEX to develop recommendations in order to avoid the significant variation in clinical practice worldwide [13].

Preoperative considerations

Participation in a specialised advanced pelvic cancer MDT meeting is compulsory for high-risk and intricate cases, such as those with LARC or LRRC [9,14-16].

Several studies have indicated a link between enhanced survival rates and discussions during MDT meetings, especially in the case of complex rectal cancers [14,17]. MDT meetings offer additional advantages, including improved communication among clinicians, access to the latest treatments, education and training, and better coordination of care. Although they are essential for the treatment of patients with complex cancer, the substantial resources needed to conduct these meetings must be considered in service planning [12].

Ideally, the core team includes an MDT lead or chair such as a colorectal, gynaeoncology, or urology consultant, an MDT coordinator or secretary, at least two colorectal surgeons, a gynaeoncologist, an urologist, a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, a histopathologist, a radiologist, and clinical nurse specialists. Depending on the case, additional specialists may be invited [18].

Staging of LARC and LRRC should be based on the TNM cancer system [19-21]. Pelvic MRI is the most accurate test to define locoregional spread, local lymph node status and response to therapy with EUS having less value and being used complementary or when MRI is contraindicated [19-22]. For assessing for distant metastases, CT of the chest and CT or MRI of the abdomen are considered efficient [19-21]. In LRRC, or when a pelvic exenteration procedure is planned, a PET-CT may be considered [10,19].

For restaging purposes after neoadjuvant therapy, although repeating the initial staging imaging modalities is essential and is strongly recommended, advanced functional MRI techniques and/or a PET-CT scan should also be considered [19,21,22].

For LARC considered for PE, neoadjuvant treatment is considered mainstream. The 3 commonest regimes are total neoadjuvant treatment (TNT), long course chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and short course radiotherapy (SCRT). National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) suggests TNT [21], while European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) suggests either CRT or SCRT [20]. American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCR) suggests CRT over SCRT, with no suggestions regarding TNT [19].

For LRRC, data is limited. According to ESMO [20], in non irradiated patients planned for surgical resection, a standard-dose CRT or a SCRT followed by chemotherapy is recommended, while in patients who have already received radiation therapy, re-irradiation with lower doses plus chemotherapy is a viable option. A 2022 meta-analysis [23] demonstrated that for LRRC, CRT followed by surgery can improve resection status, long-term disease control, and survival rates.

Patients undergoing PE, do not need routine admission the night before surgery, unless there is need for optimisation [13]. There is strong recommendation regarding the preoperative nutritional and fitness optimisation, which should start long before surgery [10]. It is also strongly recommended that the anaesthesiologist involved in the PE case, should personally undertake the pre-assessment of the patient [10].

CPET is an effective pre-assessment tool, since it can risk-stratify patients and can be a useful predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality [24]. Should it be unavailable, MET assessment is a viable but less accurate method [13]. Other pre-assessment modalities can be offered based on the comorbidities of each patient.

Immediately preoperatively, a regular dedicated specialist team including the anaesthesiologic, the surgical and the nursing staff, the use of the World Health Organization (WHO) Surgical Checklist and a team brief are essential to ensure good communication and teamwork and to improve patient outcomes [13]. If the case is anticipated to exceed 12 hours, a second anaesthesiologic consult or senior trainee is advised to assist [10].

Intraoperative Considerations

Patient positioning is of great importance to reduce pressure induced injuries like neuropathies, ulcers and Well leg compartment syndrome (WLCS) [25,26]. Use of pads on pressure points, quality operating tables and mattresses, avoidance of joint over manipulation are important preventive strategies [27].

Regarding anaesthesia, the current consensus is the administration of inhaled volatile anaesthetics; use of total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) is not suggested despite its advantages in the postoperative period [13]. In the operating theater, intensive monitoring of the patient is warranted and except the Anesthesiology Control Tower, other modalities like ABG, Rapid Infusers and Thromboelastography (TEG) machines are essential to be readily approachable by the anaesthesiologists by being situated inside or very close to the OR [13].

Patients undergoing PE are very likely to need transfusion of a variety of blood products including pRBCs, FFP and platelets and it should be guided by TEG, if available [10]. Two cross-matched pRBCs are required as a minimum before commencing every case [13]. Tranexamic acid is a useful aid for hemorrhage prevention but with serious complications including death and thromboembolic events [28]. A maximum of 1g is recommended and it can reduce the bleeding by one third; its action varies by timing of administration but it’s not statistically significant [29].

For prevention of VTE and Pulmonary embolism, IPCs and TEDs are imperative; prophylactic LMWH should be routinely administered within 24 h of the perioperative period but the consensus is low and it should be individualised for each patient [13].

The essential technical elements of extended and exenteration pelvic surgery should be clearly defined in a standardised thesaurus (Pelvic Exenteration Lexicon), which will enhance data synthesis, enable precise activity documentation for audits, and ultimately lead to better patient outcomes [30,31].

Plastic reconstruction after a PE procedure is complex and should weigh many factors, including the status of the patient, the size of the pelvic and perineal defect, any history of irradiation or previous chemotherapy and the plan for postoperative adjuvant therapy [30,32]. Several approaches have been suggested for reconstructing the pelvic floor and vulvovaginal complex in females.

The Vertical Rectus Abdominis (VRAM) flap followed by the Inferior Gluteal Artery Myocutaneous (IGAM) flap are the most frequently used flaps [33]. Other commonly used techniques are the Transverse Rectus Myocutaneous flap, the Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator flap, gluteal flaps (Superior/ Inferior Gluteal Artery Perforator flap, Internal Pudendal Artery Perforator flap or Perineal Turnover flap) and thigh flaps (i.e. Anterolateral Thigh flap, Tensor Fascia Lata flap, Gracilis flap, De-epithelised Gracilis Adipofascial flap) [30,34-37]. However, until now, there is no optimal method and even the most advanced techniques fail to fully restore both form and function [38].

Use of the omentum as a pedicle flap, is another option, which can serve as a pelvis filler and can be used as an adjunct when the tissue deficit is quite large or when less invasive reconstructive techniques are selected like primary closure, skin grafts or local skin flaps [39-41]. In selected cases, a primary closure or a bioprosthetic mesh can also be utilised [32]. In cases of neovaginal reconstruction, a bilateral gluteal advancement flap or a VRAM flap are recommended [33].

Following repeat PE for LRRC, re-do reconstruction is challenging, and largely depends on the extent of resection needed to achieve negative margins and the chosen method of primary reconstruction [30].

Urinary reconstruction should effectively maintain renal function, ensure proper urinary outflow, and minimize patient morbidity [42]. In contemporary practice, the most frequently utilised urinary diversions are the ileal conduit (Bricker procedure) and the colon conduit [43]. Though infrequently used, the double barrel wet colostomy is another option [44].

Postoperative considerations

Achieving satisfactory postoperative analgesia can be complex and should employ a multimodal, opioid-sparing approach whenever possible; various analgesic techniques, such as epidural or spinal analgesia, intravenous lidocaine, transversus abdominis plane block, and continuous local anaesthetic wound infusion are effective for postoperative pain control, each with its own risks and benefits [45]. Regional anaesthesia should be carefully monitored by practitioners skilled in managing and adjusting epidural pain management as needed [13].

PE has a well-documented and profound impact on patients with advanced pelvic malignancy with a high morbidity (~18%-87% ) and a 30- day mortality between 0% and 9.1% [46]. Additionally, it diminishes Quality of Life (QoL), and physical functioning may never fully return to previous levels [47].

Complications can have various origins, including the perineum and the wound trauma, the renal system, the gastrointestinal tract, the cardiovascular and the pulmonary system. Their frequency depends on several factors such as the previous morbidities of the patient, the choice of urological and perineal reconstruction, the surgical technique and the extent of pelvic resection, the perioperative care of the patient, etc [48].

There is an emerging interest in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) as a method for assessing the impact and outcomes of the surgery [10]. Commonly used questionnaires include the AQoL, QLQ-C30, SF-36®, SF-6D®, FACT-C, and the distress thermometer [46]. Although their use has increased over time, there remains a need for standardised use and timing of PROMs to facilitate multicenter studies [49].

Patients undergoing PE typically require transfer to the ICU postoperatively, preferably intubated, for invasive monitoring since they often experience a significant SIRS, which can lead to hemodynamic instability [13].

Post-operative surveillance specific to PE has yet to be established, but follow-up should generally align with protocols for primary rectal cancer and it is best conducted by the surgeon who performed the operation, since they are familiar with the intricacies of the case, with further consultation of other members of the MDT if imposed by the clinical case [10]. Patients are typically kept under medical surveillance for a minimum of five years, and there is no evidence suggesting that a shorter-interval follow-up schedule should be routinely used in more complex cases [10].

In Greece, the National Health System lucks centralisation of complex cancer surgery into high-volume centres. There are severe and widening disparities across the country and survival rates remain unacceptably poor for cancer patients. There are challenges and equally opportunities that are needed to develop radical, yet sustainable plans, which are comprehensive, evidence-based, integrated, patient-outcome focused, and deliver value for money.

Limitations

Although our survey was distributed to the members of the Greek Society of Coloproctology and the Hellenic Surgical Society, the actual responding population cannot be described, and respondents with biases may select themselves into the sample. Additionally, lack of centralisation of cancer services precludes accurate national data and comparisons of results, between different units, and there is insufficient information on the patient-selection process, the criteria for resectability and the peri operative outcomes [11] .

CONCLUSION

Pelvic exenteration surgery has significantly evolved over recent decades, transitioning from a palliative procedure in gynaecologic practice to a potential curative option for patients with advanced pelvic malignancies. It is now considered the standard of care for surgical oncologists for patients with locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. However, there is great diversion in clinical practice and treatment protocols among exenteration centres.

Although guidelines in this field have already been published, further studies are needed in various aspects of the perioperative and anaesthetic management of patients undergoing pelvic exenteration procedures. Such complex procedures are also imperative to be centralised, and specialised exenteration centres should be established to ensure standardisation and that quality standards are met.

As stated by Kontovounisios, 2024 [50], “the triad of success in PE surgery, encompassing objective measures such as survival, and subjective measures including quality of life and health economics, is based around “one-third selection process, one third decision-making and one-third surgical technique”.

Incorporating collaboration, teaching, and research opportunities into the “one-third selection process, one-third decision-making, and one-third surgical technique” triad will enable specialist surgeons to perform more precise surgery in dedicated institutions and will offer compassionate care through a clinical approach focused on direct personal interaction with patients.

Conflict of interest: None

REFERENCES

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Statistics | How Common Is Colorectal Cancer? [Internet] [Accessed 2024 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- OECD. EU Country Cancer Profile: Greece 2023. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1787/30b7e1f9-en

- ECIS – European Cancer Information System. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in 2022, for all countries [Internet] [Accessed: 2024 Aug 30]. Available from: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/explorer.php?$0-0$1-All$4-1,2$3-13$6-0,85$5-2022,2022$7-7$2-All$CEstByCountry$X0_8-3$X0_19-AE27$X0_20-No$CEstBySexByCountry$X1_8-3$X1_19-AE27$X1_-1-1$CEstByIndiByCountry$X2_8-3$X2_19-AE27$X2_20-No$CEstRelative$X3_8-3$X3_9-AE27$X3_19-AE27$CEstByCountryTable$X4_19-AE27

- Rutten HJ, den Dulk M, Lemmens VE, van de Velde CJ, Marijnen CA. Controversies of total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer in elderly patients. Lancet Oncol. 2008 May;9(5):494-501.

- Keller DS. Staging of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Beyond TME. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020 Jun;33(5):258–67.

- Oronsky B, Reid T, Larson C, Knox SJ. Locally advanced rectal cancer: The past, present, and future. Semin Oncol. 2020 Feb;47(1):85-92.

- Spratt JS, Watson FR, Pratt JL. Characteristics of variants of colorectal carcinoma that do not metastasize to lymph nodes. Dis Colon Rectum. 1970 May-Jun;13(3):243-6.

- Brunschwig A. Complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma; A one-stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomy. Cancer. 1948 Jul;1(2):177-83.

- Kontovounisios C, Tekkis P. Locally Advanced Disease and Pelvic Exenterations. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017 Nov;30(5):404-14.

- PelvEx C. Minimum standards of pelvic exenterative practice: PelvEx Collaborative guideline. Br J Surg. 2022 Nov;109(12):1251-63.

- Kontovounisios C, Tan E, Pawa N, Brown G, Tait D, Cunningham D, et al. The selection process can improve the outcome in locally advanced and recurrent colorectal cancer: Activity and results of a dedicated multidisciplinary colorectal cancer centre. 2017;19(4):331-8. Colorectal Dis. 2017 Apr;19(4):331-8.

- PelvExCollaborative. Pelvic Exenteration for Advanced Nonrectal Pelvic Malignancy. Ann Surg. 2019 Nov;270(5):899-905.

- PelvExCollaborative. Perioperative management and anaesthetic considerations in pelvic exenterations using Delphi methodology: Results from the PelvEx Collaborative. BJS Open [Internet]. 2021;5(1). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/bjsopen/article/5/1/zraa055/6137382?login=false

- Prades J, Remue E, van Hoof E, Borras JM. Is it worth reorganising cancer services on the basis of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)? A systematic review of the objectives and organisation of MDTs and their impact on patient outcomes. Health policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2015 Apr;119(4):464-74.

- Obias VJ, Reynolds HL, Jr. Multidisciplinary teams in the management of rectal cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007 Aug;20(3):143–7.

- Selby P, Popescu R, Lawler M, Butcher H, Costa A. The value and future developments of multidisciplinary team cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019 Jan:39:332-40.

- Nicholls J. The multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis.2008 May;10(4):311-3.

- [NICE] NIfHaCE. Colorectal cancer [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng151

- You YN, Hardiman KM, Bafford A, Poylin V, Francone TD, Davis K, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020 Sep;63(9):1191-222.

- Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown G, Rodel C, Cervantes A, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_4):iv22-iv40.

- Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Azad N, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, et al. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022 Oct;20(10):1139-67.

- Shur JD, Qiu S, Johnston E, Tait D, Fotiadis N, Kontovounisios C, et al. Multimodality Imaging to Direct Management of Primary and Recurrent Rectal Adenocarcinoma Beyond the Total Mesorectal Excision Plane. Radiol Imaging Cancer. 2024 Mar;6(2):e230077.

- Fadel MG, Ahmed M, Malietzis G, Pellino G, Rasheed S, Brown G, et al. Oncological outcomes of multimodality treatment for patients undergoing surgery for locally recurrent rectal cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022 Sep;109:102419.

- Moran J, Wilson F, Guinan E, McCormick P, Hussey J, Moriarty J. Role of cardiopulmonary exercise testing as a risk-assessment method in patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2016 Feb;116(2):177-91.

- Haisley M, Sørensen JA, Sollie M. Postoperative pressure injuries in adults having surgery under general anaesthesia: systematic review of perioperative risk factors. Br J Surg. 2020 Mar;107(4):338-47.

- Gill M, Fligelstone L, Keating J, Jayne DG, Renton S, Shearman CP, et al. Avoiding, diagnosing and treating well leg compartment syndrome after pelvic surgery. Br J Surg. 2019 Aug;106(9):1156-1166.

- McEwen DR. Intraoperative positioning of surgical patients. AORN journal. 1996 Jun;63(6):1059-63, 66-79; quiz 80-6.

- Painter TW, McIlroy D, Myles PS, Leslie K. A survey of anaesthetists’ use of tranexamic acid in noncardiac surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2019 Jan;47(1):76-84.

- Ker K, Prieto-Merino D, Roberts I. Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of tranexamic acid on surgical blood loss. Br J Surg. 2013 Sep;100(10):1271-9.

- Giannas E, Kavallieros K, Nanidis T, Giannas J, Tekkis P, Kontovounisios C. Re-Do plastic reconstruction for locally advanced and recurrent colorectal cancer following a beyond Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) Operation-Key Considerations. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb;13(5):1228.

- Burns EM, Quyn A. The ‘Pelvic exenteration lexicon’: Creating a common language for complex pelvic cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2023 May;25(5):888-96.

- Buscail E, Canivet C, Shourick J, Chantalat E, Carrere N, Duffas JP, et al. Perineal wound closure following abdominoperineal resection and pelvic exenteration for cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Feb;13(4):721.

- PelvEx Collaborative. A review of functional and surgical outcomes of gynaecological reconstruction in the context of pelvic exenteration. Surg Oncol. 2024 Feb:52:101996.

- Choi J, Kim RY, Lee CR, Choi JY, Moon S-H, Oh DY, et al. Reconstruction and Management Strategies for Pelvic Ablative Surgery. J Wound Manag Res. 2024;20(1):55-62.

- Faur IF, Clim A, Dobrescu A, Prodan C, Hajjar R, Pasca P, et al. VRAM Flap for Pelvic Floor Reconstruction after Pelvic Exenteration and Abdominoperineal Excision. J Pers Med. 2023 Dec;13(12):1711.

- Zhang C, Yang X, Bi H. Application of depithelized gracilis adipofascial flap for pelvic floor reconstruction after pelvic exenteration. BMC Surg. 2022 Aug;22(1):304.

- Kaartinen IS, Vuento MH, Hyoty MK, Kallio J, Kuokkanen HO. Reconstruction of the pelvic floor and the vagina after total pelvic exenteration using the transverse musculocutaneous gracilis flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015 Jan;68(1):93-7

- Hellinga J, Stenekes MW, Werker PMN, Janse M, Fleer J, van Etten B. Quality of life, sexual functioning, and physical functioning following perineal reconstruction with the lotus petal flap. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020 Dec;27(13):5279-85

- Miyamoto Y, Akiyama T, Sakamoto Y, Tokunaga R, Ohuchi M, Shigaki H, et al. Omental flap after pelvic exenteration for pelvic cancer. Surg Today. 2016 Dec;46(12):1471-5.

- Hultman CS, Sherrill MA, Halvorson EG, Lee CN, Boggess JF, Meyers MO, et al. Utility of the omentum in pelvic floor reconstruction following resection of anorectal malignancy: patient selection, technical caveats, and clinical outcomes. Ann Plast Surg. 2010 May;64(5):559-62.

- Kusiak JF, Rosenblum NG. Neovaginal reconstruction after exenteration using an omental flap and split-thickness skin graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996 Apr;97(4):775-81; discussion 783-3.

- Lee RK, Abol-Enein H, Artibani W, Bochner B, Dalbagni G, Daneshmand S, et al. Urinary diversion after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Options, patient selection, and outcomes. BJU Int. 2014 Jan;113(1):11-23

- Hagemans JAW, Voogt ELK, Rothbarth J, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Kirkels WJ, Boormans JL, et al. Outcomes of urinary diversion after surgery for locally advanced or locally recurrent rectal cancer with complete cystectomy; ileal and colon conduit. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Jun;46(6):1160-6.

- Wright JP, Guerrero WM, Lucking JR, Bustamante-Lopez L, Monson JRT. The double-barrel wet colostomy: An alternative for urinary diversion after pelvic exenteration. Surgeon. 2023 Dec;21(6):375-80.

- Xu W, Varghese C, Bissett IP, O’Grady G, Wells CI. Network meta-analysis of local and regional analgesia following colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2020 Jan;107(2):e109-2.

- Maudsley J, Clifford RE, Aziz O, Sutton PA. A systematic review of oncosurgical and quality of life outcomes following pelvic exenteration for locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2024 Feb Online ahead of print.

- Rausa E, Kelly ME, Bonavina L, O’Connell PR, Winter DC. A systematic review examining quality of life following pelvic exenteration for locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2017 May;19(5):430-6.

- Pleth Nielsen CK, Sørensen MM, Christensen HK, Funder JA. Complications and survival after total pelvic exenteration. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022 Jun;48(6):1362-7.

- Denys A, van Nieuwenhove Y, Van de Putte D, Pape E, Pattyn P, Ceelen W, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after pelvic exenteration for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2022 Apr;24(4):353-68.

- Kontovounisios C. Dictum of Success in Pelvic Exenterative Surgery. Hell J Surg. 2024 Jan-Mar;94(1):5–6.