Case Report

Hell J Surg. 2025 Jan-Mar;95(1):28–35

doi: 10.59869/25057

Vasiliki Angeli1, Dimitris Liatsos1, Maria Theochari2, Chrysoula Glava3, Tania Triantafyllou1, Dimitrios Theodorou1

1Department of Surgery, Hippocration General Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece

2Department of Oncology, Hippocration General Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece

3Department of Pathology, Hippocration General Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece

Correspondence: Dimitris Liatsos, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Sotiri Petroula 40, 14121, Iraklion, Athens, e-mail: dimitrisliatsos1@hotmail.com

Abstract

Mixed Neuroendocrine-Non-Neuroendocrine Neoplasm (MiNEN) of the oesophagus is an especially rare malignancy. It is composed of an adenomatous and a neuroendocrine aspect. Each histologic subtype contributes at least 30% of the immunohistopathologic features to the complex profile of these mixed neoplasms. Given the small number of cases in the existing literature and the lack of international guidelines, diagnosis and treatment may vary among different centers; however, a combined approach based on surgical resection and systemic therapies is usually the preferred pathway. In this paper, we present the case of a 68-year-old male who was initially diagnosed with oesophageal adenocarcinoma and was treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and oesophagectomy. After the histopathologic examination of the specimen, the tumour was histologically characterised as MiNEN and the patient underwent adjuvant therapy. Multimodal management and tailored treatment are essential in these complex cases since preoperative staging poses challenges and limitations.

Key Words: Mixed oesophageal neoplasm, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical treatment, adjuvant chemotherapy

Submission: 13.03.2025, Acceptance: 02.07.2025

Introduction

Oesophageal cancer is the eighth most frequently diagnosed cancer globally. The high mortality rate of this type of cancer is due to the advanced stage at presentation [1-3]. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma are the most common histologic types. Other less frequent types are neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs), lymphomas and sarcomas. Another rare type of oesophageal cancer is mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN).

Adenocarcinoma is the second most common neoplasia of the oesophagus and is associated with several risk factors, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the Caucasian race, obesity and tobacco use [1,2].Typical symptomatology of adenocarcinoma includes worsening dysphagia, unintentional weight loss and fatigue [1,2]. In most cases, the symptoms appear at an already advanced stage, with poor prognosis [1,2]. Adenocarcinoma presents an aggressive pattern of metastasis and affects regional lymph nodes, the liver, the peritoneum and in rare cases the brain [1]. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma has a consistent cytokeratin expression pattern of CK7+, CK19+ and CK20- (3258 WHO) [4].

On the other hand, oesophageal NEC is a rare type of oesophageal cancer mainly located in the middle and distal oesophagus [5,6]. Most patients remain asymptomatic, whereas dysphagia, weight loss and abdominal discomfort may be present.NEC is usually positive on histologic findings for chromogranin A, synaptophysin and CD56. Proliferation marker Ki67 or a mitosis index higher than 20% contribute to the diagnosis. A percentage lower than 20% indicates neuroendocrine tumour (NET) [8]. NEC most commonly metastasises to regional or distant lymph nodes or the liver [5,6].Although there is no consensus on the optimal treatment algorithm, a combination of neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemo/chemoradiotherapy and surgical resection is the most common treatment approach [5,6,8]. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network(NCCN) guidelines for neuroendocrine carcinomas, also with MiNEN and large or small cell carcinomas, CT or MRI scans are used to evaluate whether the tumour is resectable, in which case the treatment includes a combination of surgical resection, adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, based on etoposide and platinum based chemotherapy, and radiation or chemotherapy and chemoradiation alone, all followed by strict surveillance of the patient on a three-six month basis. In contrast, neoplasms found to be locoregional but unresectable or metastatic are treated using chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy and targeted therapy, also followed by surveillance ranging from a monthly to a four month basis [9].

MiNEN of the oesophagus is a histologically heterogeneous neoplasm that presents both adenomatous and neuroendocrine differentiation, which are identified both morphologically and immunohistochemically (by synaptophysin and/ or chromogranin expression), each representing at least 30% of the tumour [4,10]. MiNEN is three to four times more common in men. Oesophageal MiNEN is extremely rare [10]. This malignancy is diagnosed microscopically with the use of neuroendocrine (CD56, chromogranin and synaptophysin) and non-neuroendocrine (CK7, CK20 and CEA) markers [10]. Due to the rarity of this malignancy, there are no specific treatment guidelines. Hence, the treatment plan is individualized and primarily tailored for the most aggressive component of the tumour, which could be either the adenomatous or the neuroendocrine component [11]. In our case, the neuroendocrine component was identified as the more aggressive element.

In this case report, we present a 61-year-old male patient with oesophageal cancer that underwent oesophagectomy, but was eventually diagnosed with MiNEN on histopathological examination. The aim of this report is to demonstrate this rare type of oesophageal cancer as well as the importance of personalised treatment to achieve the best possible prognosis.

Case Report

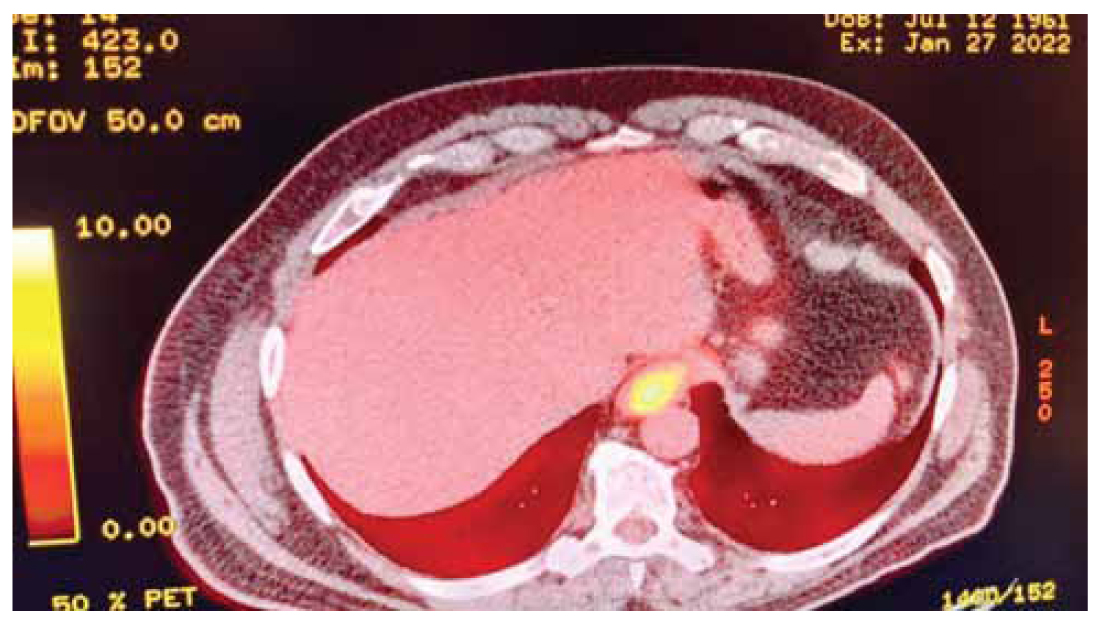

A 61-year-old male patient presented to the hospital reporting three-month worsening dysphagiato solid food, and unintentional weight loss of 6 kilograms within two months. Biochemical examination showed mild anaemia- haematocrit (37%), hemoglobin (11,8 g/dl), MCV (70,9 fL), MCH (22,6 pg/cell) and elevated CRP (96,3 mg/L). Tumour markers CEA and CA19-9 were found to be mildly elevated (22,3 ng/ml and 59,1 IU/ml respectively). The patient’s personal history included arterial hypertension and an angioplasty that had taken place 15 years prior. Firstly, a CT scan reported a mass at the level of the gastroesophageal junction. A PET/CT scan was then performed which revealed a lesion on the cardioesophageal junction with high 18F-FDG uptake (cT3N0M0) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PET/CT scan that was performed when the patient was firstly diagnosed with the disease. A lesion with high absorption of 18F-FDG and thus elevated SUVmax can be observed in the gastroesophageal junction.

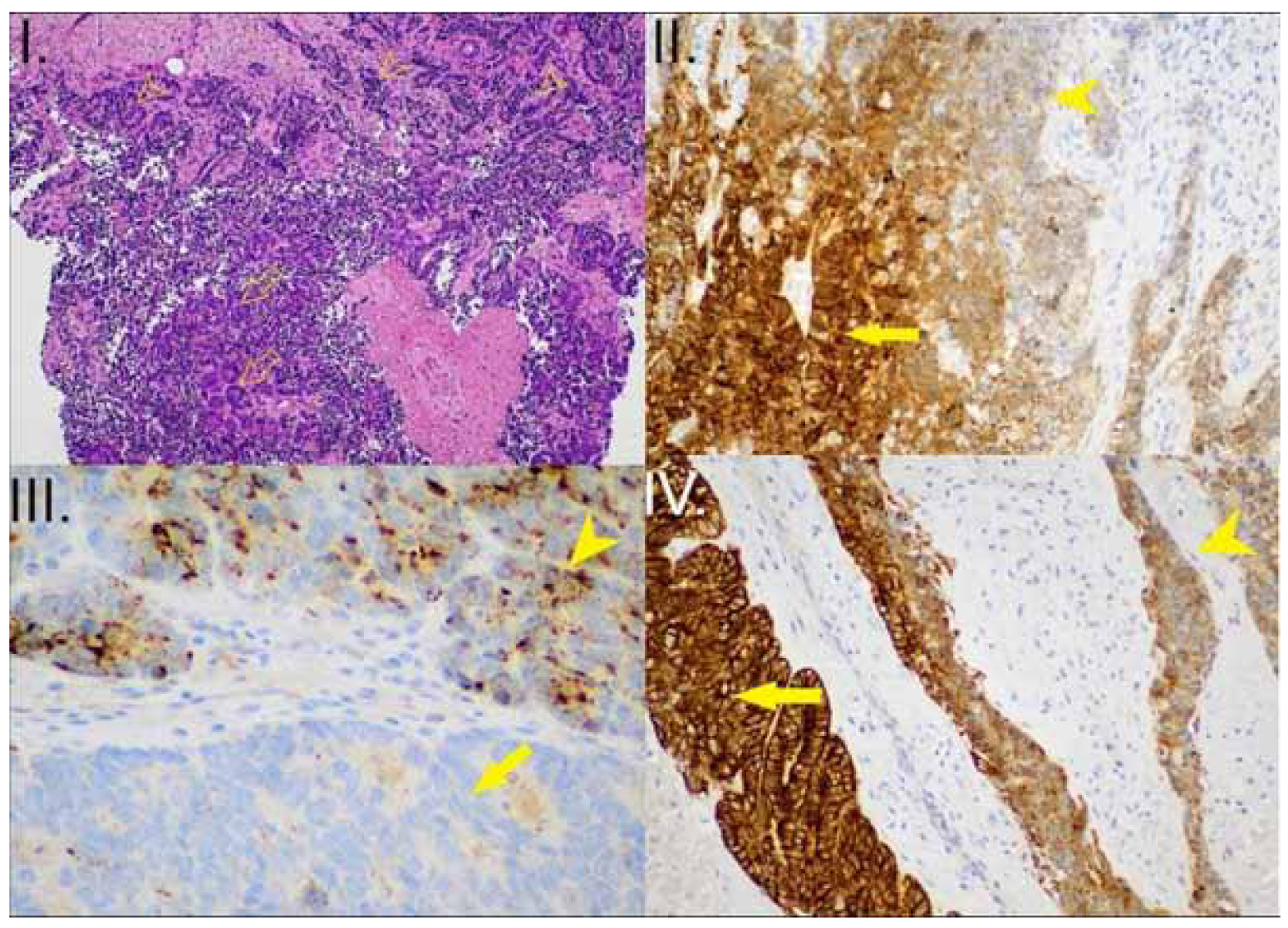

Histology of the lesion disclosed adenocarcinoma, positive for HER-2 expression with a HER-2 score of 3+, and the patient underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy with four cycles of the FLOT scheme, consisting of fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and docetaxel. After restaging, the patient underwent Ivor Lewis oesophagectomy. Surprisingly, the histopathology of the specimen showed MiNEN. More precisely, the tumour was a combination of 40% adenocarcinoma with moderate differentiation while the rest 60% was composed by large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma(LCNEC), with medium-to-large sized atypical cells, prominent nucleoliand increased number of mitosis (>20 mitosis/ 10 HPF), which were organised in rosetoid-like and solid formations with central necrosis. The tumour was invading both the submucosal layer and the muscle wall of the oesophagus and was located 2,5 cm above the z-line, measuring 4,9 cm x 2,9 cm. Six out of 17 perigastric lymph nodes were infiltrated by the adenocarcinomatous aspect of the lesion, whereas a periesophageal lymph node was infiltrated by the neuroendocrine aspect of the cancer. Therefore, the TNM staging was pT2N3. Immunohistochemical evaluation of the specimen indicated positivity for CK7 and CK8/ 18 in the adenocarcinoma component and positivity for chromogranin, synaptophysin in few cells and CD56 in the LCNEC component. The Ki-67 index of cell proliferation was 80% for the neuroendocrine part of the tumour and 55% for the adenocarcinoma (Figure 2).

Figure 2. I. Mixed Neuroendocrine-Non-Neuroendocrine Neoplasm (MiNEN) (HE x100): The epithelial component is a high-grade adenocarcinoma (arrows). The neuroendocrine component is a Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (LCNEC) (arrowheads) II. MiNEN (CK7 x200): positive in the adenocarcinoma component (arrow) and negative in the LCNEC (arrowhead) III. MiNEN (Chromogranin x200): negative in the adenocarcinoma component (lower part of the image – arrow), positive in the LCNEC (Antibody binds acidic glycoproteins in the soluble fraction of neurosecretory granules – arrowhead) IV. MiNEN (CK8/ 18 x200): intense, diffuse pattern of expression in the adenocarcinoma component (arrow), granular pattern of expression in the LCNEC (arrowhead).

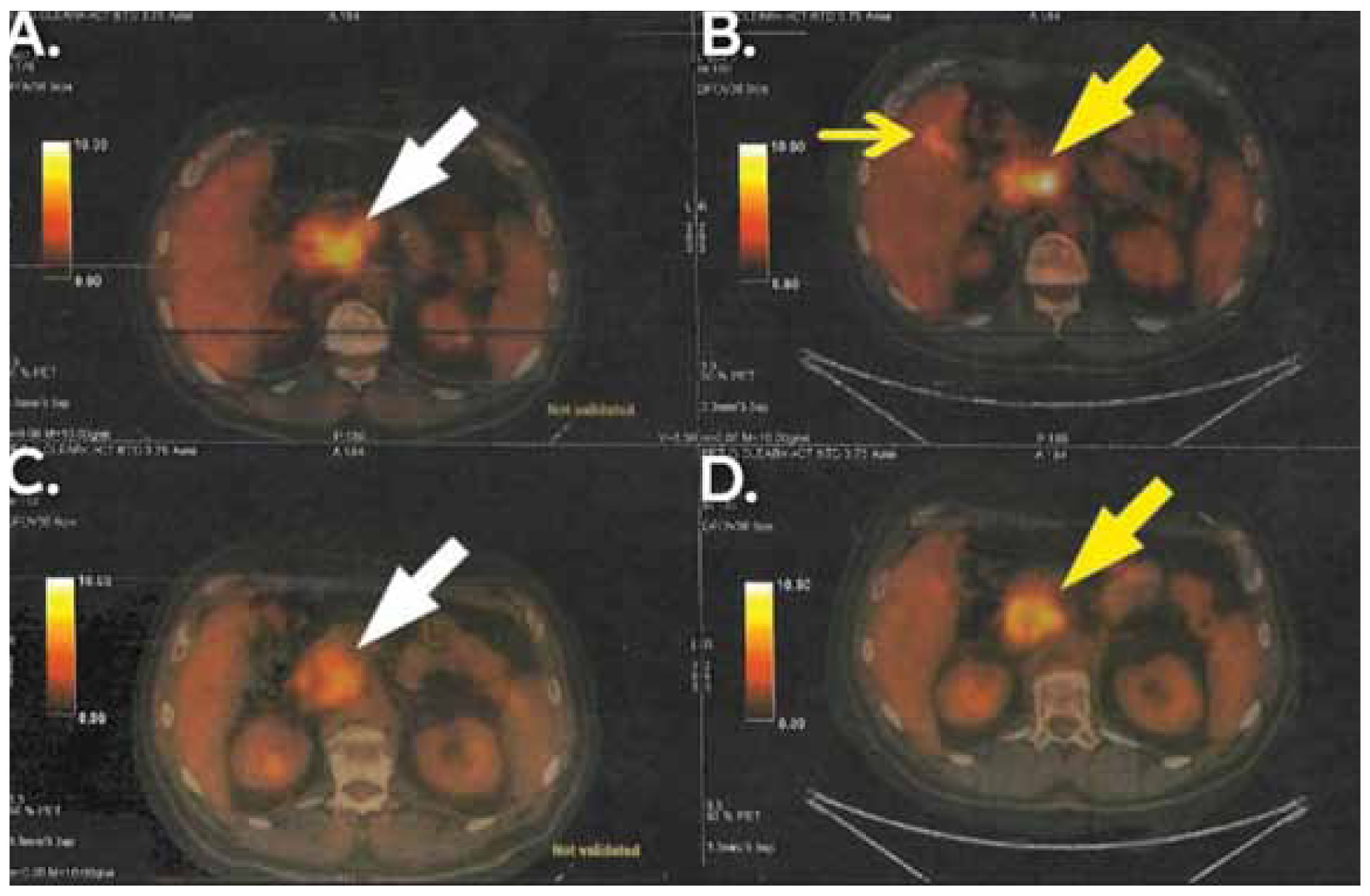

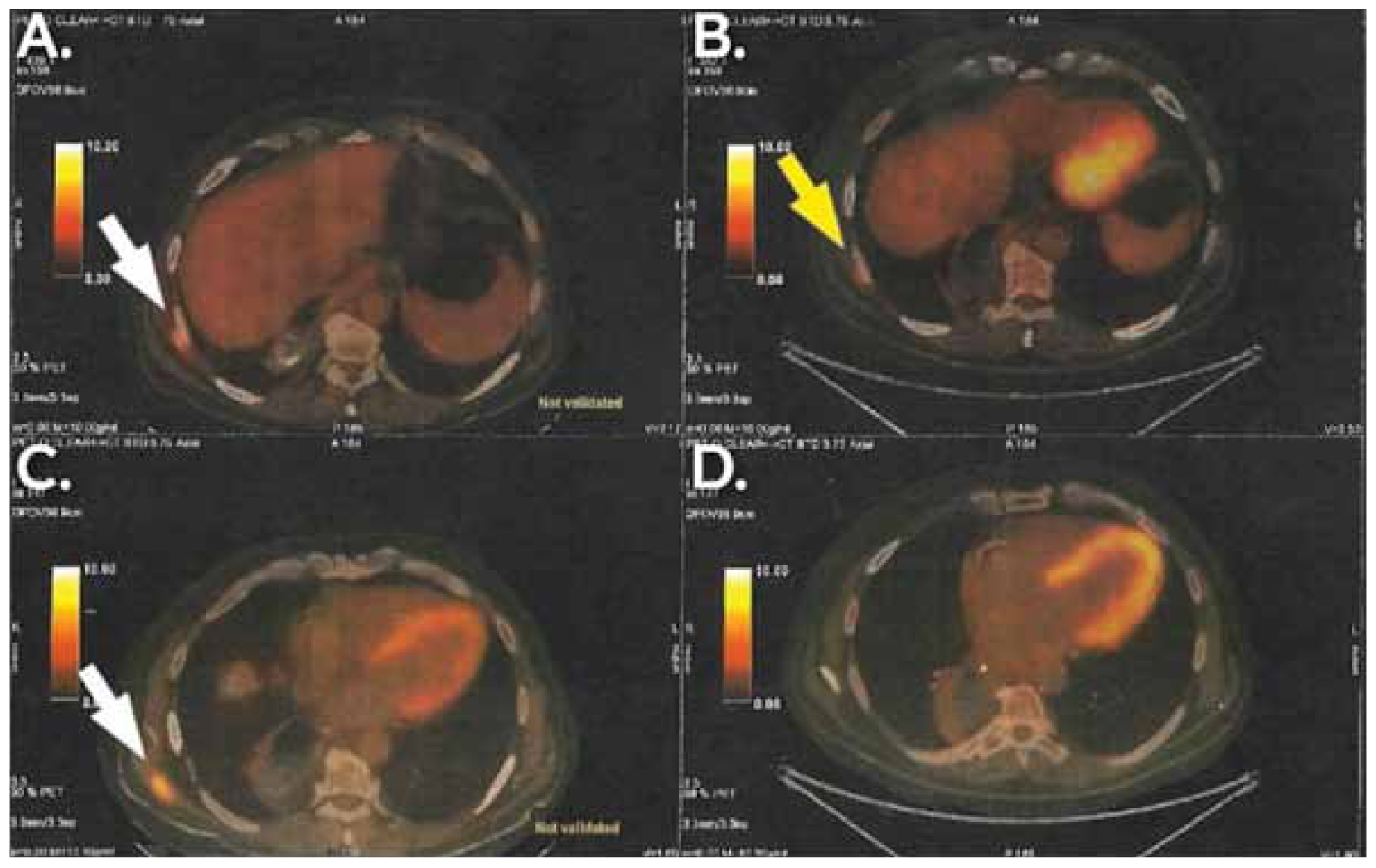

Targeted chemotherapy for the neuroendocrine component of the tumour was added, consisting of three cycles of carboplatin and etoposide. A few months later, a routine follow-up PET/CT scan revealed an enlarged lymph node at the left paraaortic space (5,4 x 3,6 cm and SUVmax: 10.8), an enlarged lymph node behind head of the pancreas (1 x 0,8 cm and SUVmax: 3,2) and a high 18F-FDG uptake nodular lesion at the left posterolateral thoracic wall (0,9 x 0,4 cm and SUVmax: 3,3). Following multidisciplinary meeting and multimodal decision-making, cisplatin, pembrolizumab and herceptin were administered. A second PET/CT scan was performed a few weeks later and confirmed that the metastatic lesions had exhibited no progression. At the same time, a new metastasis was identified in the right latissimus dorsi (2,7 x 1,8 cm and SUVmax: 8,1). The figures below depict the differences between the first and the second PET/CT scan that were done post-operatively (Figures 3,4).

Figure 3. PET/CT showing the findings after the first and the second schemes of adjuvant therapy and their relapses, respectively (B and D show the first relapse and A and C show the second relapse). Enlarged paraaortic lymph nodes and a mass in the lumen of the right colic flexure(big and small yellow arrow in B) and enlarged lymph nodes behind the margin of the head and body of the pancreas (big yellow arrow in D) were findings of the first relapse. Further enlarged paraaortic lymph nodes with higher SUVmax(big white arrow in A) and further enlarged posterior pancreatic lymph nodes, behind the margin of the head and body of the pancreas, (big white arrow in C) were findings of the second relapse.

Figure 4. PET/CT showing the findings after the first and the second schemes of adjuvant therapy and their relapses respectively(B and D show the first relapse and A and C show the second relapse). Subcutaneous mass in the lateral and posterior thoracic wall (big yellow arrow in B) was the finding of the first relapse. An even larger subcutaneous mass in the lateral and posterior thoracic wall (white arrow in A) and an independent mass in the posterior thoracic wall in contact with latissimus dorsi (white arrow in C, absent in D) were the findings of the second relapse.

After the second PET/CT scan, an excisional biopsy was performed on the right subcutaneous thoracic lesion. The findings were consistent only with the adenocarcinomatous type of cancer and therefore famderuxtecan was administered.

During the following months, the patient underwent various follow-up PET/CT and MRI scans which showed a variety of results, including both progression and regression of the lesions and also received many different therapeutic regimens. The most recent PET/CT scan shows worsening of the patient’s lesions and new findings including nodular masses in the upper lobe of the right lung and pleura and a lesion anterior to the left adrenal gland. Currently the patient is still under therapy with Nivolumab and Abraxane.

Discussion

MiNEN constitutes only a small percentage of oesophageal neoplastic diseases. Nevertheless, its non-specific symptomatology, the increased difficulty of differential diagnosis with other types of cancer of the oesophagus and the need for individualised therapy make it an interesting clinical entity [10]. In our case there are several teaching points. Firstly, regarding the expression of biomarkers, the main characteristics of the patient’s lesion were positivity for HER-2 (score: 3+) and negativity for Microsatellite Instability (MSI). Biomarkers are a useful tool that can be used for the prognosis and the treatment of oesophageal cancer [12-14]. Specifically, there are many immunohistochemical methods that can determine which biomarkers are expressed by the tumour cells. Of particular interest are PD-L1, CTLA-4, HER-2 and MSI. Firstly, the PD-1/ PD-L1 system has a negative prognostic value, since it is associated with higher recurrence rates post-operatively, as it inhibits the function of anti-tumour immune T-cells and leads to proliferation of malignant cells [12,13]. This system can be used as a target for immunotherapeutic schemes in neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment, implementing either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 agents, such as pembrolizumab and avelumab respectively, which activate the patient’s immune system, by triggering a T-cell dominant response that is more tumour-specific [13,14]. Despite its efficacy as shown by clinical trials, this method of immunotherapy was until recently mainly used for advanced metastatic patients and therefore needs further investigation before perioperative implementation as a standard way of treatment [12,13]. Similar to PD-1/ PD-L1, CTLA-4 is another biomarker, located on T-cells, which also inhibits their function when bound to proteins expressed by cancer cells. Inhibitory monoclonal antibodies such as ipilimumab prevent the upregulation of CTLA-4 [13]. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2 (HER-2) is another crucial biomarker expressed in oesophageal cancer cells, which regulates cell growth and thus constitutes an important target for targeted therapy [15]. HER-2 inhibitory drugs and namely trastuzumab show increased patient survival when used together with chemotherapeutic schemes. Lastly, Microsatellite Instability (MSI) described by deficiency of DNA-mismatch repair proteins (dMMR), although not a target for specific immunotherapy, is associated with higher overall survival for patients and therapy response, compared to Microsatellite Stable patients (MSS) [12,13].

Secondly, regarding the infiltration of the lymph nodes, both the adenocarcinomatous and the neuroendocrine part of the cancer were found to contribute to this aggressive metastatic pattern. As observed, using only imaging diagnostic techniques can lead to clinical mis-staging of the tumour. In our case, the initial CT and PET/CT that was performed was unable to detect infiltrated lymph nodes, which were later found positive for metastasis in the pathologic examination (pT2N3M0). These shortcomings that emerge from the mismatch of the cTNM and the pTNM staging have been described in the literature. CT scan is deemed unable to differentiate between T1, T2 and T3 regarding oesophageal cancer, whereas changes in adjacent structures of the oesophagus are the ones indicating T4 staging. Additionally, CT has low sensitivity for nodal staging and it is the first to be used for detection of metastasis, followed by PET, for added diagnostic value [16]. Having mentioned PET scan, it has a very low impact in determining the T category of the tumour and is characterised by high specificity but low sensitivity for nodal staging, while providing information about the metabolic activity of the tumour cells [16]. Lastly, another imaging technique is the endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), with high contribution to the tumour staging being able to define the T stage and discern more accurately between T1a and T1b, with varied sensitivity and specificity according to different papers, and it also can help determine the nodal staging, depicting the internal characteristics of infiltrated lymph nodes [16]. The low sensitivity of these imaging techniques renders histological confirmation by biopsy necessary in order to have an accurate clinical staging. However, even biopsies have limitations in detecting both components, therefore it is not uncommon to misdiagnose a tumour, as it happened in our case as well [11].

Lastly, one of the most intriguing findings is the soft tissue metastasis in the posterolateral and posterior thoracic wall at a later stage of disease progression which was successfully discovered with the use of PET/CT scan.

The existing literature on this uncommon entity remains scarce. Kawazoe T, Saeki H, Edahiro K, et al., 2018, report a case of a 70-year-old male patient with MiNEN and Barrett’s oesophagus. The patient was treated with an oesophagectomy and regional lymph node dissection [17]. According to another report, a 68-year-old man with a two month history of postprandial pain and vomiting was diagnosed with a neuroendocrine carcinoma. The tumour was positive for chromogranin. This patient was also treated with transthoracic oesophagectomy, with no neoadjuvant treatment. Later, biopsy of the resected specimen showed MiNEN [18]. Mendoza-Moreno F, Díez-Gago MR, Mínguez-García J, et al., 2018, reported a 68-year-old man with mixed adenoneuroendocrine characteristics confirmed in the specimen of oesophagectomy [10]. Golombek T, Henker R, Rehak M, et al., 2019, presented a case of a 60-year-old male with upper abdominal pain, in whom a mass in the gastroesophageal junction was found via endoscopy (Siewert type 1). Pathologic examination of the lesion confirmed it as a HER/neu positive MiNEN and further, imaging via CT and PET/CT scan showed metastasis to the liver and multiple lymph nodes. The patient underwent chemotherapy with three different regimes, (first line therapy: cisplatin and etoposide with palliative intent, with later addition of trastuzumab, second line therapy: topotecan, third line therapy: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine), with no major improvement and died due to further tumour progression and health deterioration [19]. Lastly, another paper describes a 92-year-old male patient who was diagnosed with MiNEN T1N0M0, in the context of investigation of an oesophageal lesion. Endoscopic submucosal dissection was performed and pathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of MiNEN. No further treatment was administered, and no recurrence was observed two years post-resection [20].The characteristics of these five case reports are summarised in Table 1. It is also noteworthy that histopathological differences were observed both in our case and several others, between the endoscopic biopsy and the final organ pathology, a result indicative of the difficulty to preoperatively characterise the tumour [10,18].

Oesophageal MiNENs usually consist of poorly differentiated NEC and either squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma (in Barrett mucosa or ectopic gastric mucosa) (3371 WHO) [4]. For a neoplasm to qualify as a MiNEN, both components should be morphologically and immunohistochemically (by synaptophysin and/or chromogranin expression) recognisable. Both components are usually carcinomas; therefore, the neuroendocrine component is classified as a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), which may present either large cell NEC (LCNEC) or small cell NEC (SCNEC). Carcinomas previously treated with neoadjuvant therapy are not considered MiNENs, unless the diagnosis of MiNEN is established based on a pretreatment specimen, because the neuroendocrine morphology exhibited by some treated carcinomas may not have the same prognostic significance as that seen in a de novo component of NEC [4].

In summary, despite its rarity, MiNEN is a present clinical entity, which should be part of the differential diagnosis of the clinical doctor since its differences from other oesophageal neoplasms, especially regarding its treatment, modify completely the decision-making, the treatment regimens and prognosis. Therefore, multimodal consultation and collaboration among specialists are deemed to be necessary.

Conclusions

In conclusion, MiNEN is a rare type of gastrointestinal tract cancer with positive immunohistochemical markers for both non-neuroendocrine and neuroendocrine components. In this paper, we report one of the more uncommon presentations of this oncological entity that concerns the oesophagus. Awareness and thorough endoscopic investigation and imaging studies with accurate staging are key in the final diagnosis and combination of treatment pathways. Nevertheless, the limited number of reported cases in the literature forces us to be skeptical about the protocols implemented. It is also important to highlight that, due to the complex nature of such cases, a multidisciplinary approach as well as an individualized therapeutic plan are of utmost importance. Ultimately this paper emphasises the need for further research on this clinical pathology due to the lack of literature.

References

- Rubenstein JH, Shaheen NJ. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug;149(2):302-17.e1. Doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.053

- Domper Arnal MJ, Ferrández Arenas Á, Lanas Arbeloa Á. Esophageal cancer. Risk factors, screening and endoscopic treatment in western and eastern countries. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Jul;21(26):7933-43. Doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7933

- Zhang Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep;19(34):5598-606. Doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5598

- Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020 Jan;76(2):182-8. Doi: 10.1111/his.13975

- Deng HY, Ni PZ, Wang YC, Wang WP, Chen LQ. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus: clinical characteristics and prognostic evaluation of 49 cases with surgical resection. J Thorac Dis. 2016 Jun;8(6):1250-6. Doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.04.21

- Lee CG, Lim YJ, Park SJ, Jang BI, Choi SR, Kim JK, et al. The clinical features and treatment modality of esophageal neuroendocrine tumors: A multicenter study in Korea. BMC Cancer. 2014 Aug:14:569. Doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-569

- Awada H, Hajj Ali A, Bakhshwin A, Daw H. High-grade large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2023 Apr;17(1):144. Doi: 10.1186/s13256-023-03879-0

- Egashira A, Morita M, Kumagai R, Taguchi K-I, Ueda M, Yamaguchi S, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus: Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of 14 cases. PLoS One. 2017 Mar;12(3):e0173501. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173501

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2024 Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors. 2024 [Internet]

- Mendoza-Moreno F, Díez-Gago MR, Mínguez-García J, Tallón-Iglesias B, Zarzosa-Hernández G, Fernández S, et al. Mixed Adenoneuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Esophagus: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Niger J Surg. 2018 Jul-Dec;24(2):131-4. Doi: 10.4103/njs.NJS_43_17

- La Rosa S, Marando A, Sessa F, Capella C. Mixed Adenoneuroendocrine Carcinomas (MANECs) of the Gastrointestinal Tract: An Update. Cancers (Basel). 2012 Jan;4(1):11-30. Doi: 10.3390/cancers4010011

- Wang X, Wang P, Huang X, Han Y, Zhang P. Biomarkers for immunotherapy in esophageal cancer. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 May;14:1117523. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37197663/ Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1117523

- Teixeira Farinha H, Digklia A, Schizas D, Demartines N, Schäfer M, Mantziari S. Immunotherapy for Esophageal Cancer: State-of-the Art in 2021. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jan;14(3):554. Doi: 10.3390/cancers14030554

- Li Q, Liu T, Ding Z. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for resectable esophageal cancer: A review. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2022 Dec;13:1051841. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36569908/ Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1051841

- Yang YM, Hong P, Xu WW, He QY, Li B. Advances in targeted therapy for esophageal cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020 Oct;5:229. Doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00323-3

- Jayaprakasam VS, Yeh R, Ku GY, Petkovska I, Fuqua 3rd, JL Gollub M, et al. Role of Imaging in Esophageal Cancer Management in 2020: Update for Radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020 Nov;215(5):1072-84. Doi: 10.2214/ajr.20.22791

- Kawazoe T, Saeki H, Edahiro K, Korehisa S, Taniguchi D, Kudou K, et al. A case of mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC) arising in Barrett’s esophagus: literature and review. Surg Case Rep. 2018 May;4(1):45. Doi: 10.1186/s40792-018-0454-z

- Kadhim MM, Jespersen ML, Pilegaard HK, Nordsmark M, Villadsen GE. Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma is a rare but important tumour found in the oesophagus. Case Rep Gastrointest Med [Internet]. 2016 Feb;2016:9542687. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2016/9542687 Doi: 10.1155/2016/9542687

- Golombek T, Henker R, Rehak M, Quäschling U, Lordick F, Knödler M. A Rare Case of Mixed Adenoneuroendocrine Carcinoma (MANEC) of the Gastroesophageal Junction with HER2/neu overexpression and distinct orbital and optic nerve toxicity after intravenous administration of cisplatin. Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42(3):123-7. Doi: 10.1159/000495218

- Gushima R, Miyamoto H, Imamura M, et al. Mixed Neuroendocrine Non-Neuroendocrine Neoplasm Arising in the Ectopic Gastric Mucosa of Esophagus. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2022 Dec;16(3):637-45. Doi: 10.1159/000527699