Case Series

Hell J Surg. 2025 Jan-Mar;95(1):49–54

doi: 10.59869/25061

Soukayna Bourabaa1,2, Abdellatif Settaf1,2

1General Surgery Department, Ibn Sina University Hospital, Rabat, Morocco

2Mohammed V University of Rabat, Morocco

Correspondence: Soukayna Bourabaa, e-mail: soukayna.bourabaa@um5r.ac.ma, ORCID iD – Soukayna Bourabaa: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5243-212X

Abstract

Introduction: Caustic sclerosing cholangitis represents a rare postoperative complication occurring after surgical treatment of liver hydatid cyst. It has been hypothetically attributed to the caustic effect of the scolicidal agent injected into the cyst for sterilisation, subsequently diffusing into the biliary tree through a cysto-biliary fistula.

Materials and Methods: We present a case series of 3 patients with caustic sclerosing cholangitis, observed following surgical treatment of liver hydatid cysts among 268 patients. Sterilisation of cyst content was performed using intracystic injection of 2% formalin solution in 2 cases. Caustic sclerosing cholangitis was diagnosed at 2, 3, and 7 months post-surgery by retention jaundice caused by irregular strictures of intra- and/or extra-hepatic bile ducts. Following hydatid cyst treatment, all 3 cases died, respectively, 2, 4, and 6 years after the intervention. Patients died from secondary biliary cirrhosis and 1 patient died from septic shock. Despite its relative rarity (3/268 of cases in our study), the severity of this iatrogenic complication and the unproven efficacy of cyst sterilisation maneuvers have discouraged us for years from using the intracystic injection of scolicidal solution technique for hydatid cyst sterilisation.

Discussion: Caustic sclerosing cholangitis progresses rapidly and is generally devoid of effective treatment, subsequently leading to the development of secondary biliary cirrhosis, or even cholangiocarcinoma.

Conclusion: Caustic sclerosing cholangitis is a rare and serious iatrogenic complication questioning the safety of intracystic sterilisation. Mechanical protection, combined with preoperative albendazole treatment, appears to be an effective alternative to avoid this complication.

Key Words: Case series, caustic sclerosing cholangitis, liver hydatid cyst, scolicidal agents

Submission: 17.08.2025, Acceptance: 16.11.2025

Introduction

Liver hydatid cyst (LHC) remains a significant endemic problem in Morocco and in many countries worldwide. Surgical treatment includes closed or open pericystectomy and excision of the protruding dome (EPD). Traditionally, cyst evacuation and sterilisation using scolicidal solutions were performed to eliminate viable cyst elements and prevent intra-abdominal dissemination. However, current guidelines do not mandate the use of scolicidal agents; instead, they emphasise careful protection of the surgical cavity to avoid spillage [1].

Various scolicidal agents, including hypertonic saline, formaldehyde, anhydrous ethanol, and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), may cause caustic injury if they enter the biliary tree, particularly in the presence of cysto-biliary communication (5–10% of cases) [2,3]. This can lead to hepatic stasis, edema, tissue necrosis, and histopathological changes—characteristic of caustic sclerosing cholangitis (CSC). For this reason, the use of scolicidal solutions is now largely discouraged.

Herein, we present a case series of 3 patients who developed CSC following surgical treatment of LHC. These cases were identified among 268 patients operated between 1998 and 2005. This report highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by CSC and discusses preventive measures, including the modern emphasis on avoiding scolicidal agents.

Case presentation

This is a retrospective case series of 268 patients who underwent surgical treatment for LHC in our department between January 1998 and December 2005. Inclusion criteria were all patients with one or more LHC treated surgically during this period, with available operative records and follow-up data. Patients without adequate documentation or who were lost to follow-up immediately after surgery were excluded. Follow-up was conducted through a combination of active methods (scheduled outpatient visits and telephone contact) and passive review of hospital medical records. Complications and deaths were identified through hospital readmissions, endoscopic or radiological findings, and official death certificates when available. The median follow-up for the cohort was 20 years (range: 18–25 years).

The patients ranged from 16 to 78 years old, with an average age of 45 years. The LHC was classified as CE1 stage without cysto-biliary fistula (CBF) in 61 cases (23%), CE2, CE3, CE4, and CE5 stages with a minor CB Fin 186 cases and a major CBF in 21 cases [5]. Surgical treatment was performed for all cases. Sterilisation of the cyst content was performed in 73 cases by directly introducing 20-30 cc of hydatid fluid and 10-30 cc of 2% formalin solution into the decompressed cyst. After evacuation of the cyst content, residual cavity treatment was carried out by EPD in 251 cases, total pericystectomy in 6 cases, and subtotal pericystectomy in 11 cases. In cases of existing CBF, intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) was systematically performed.

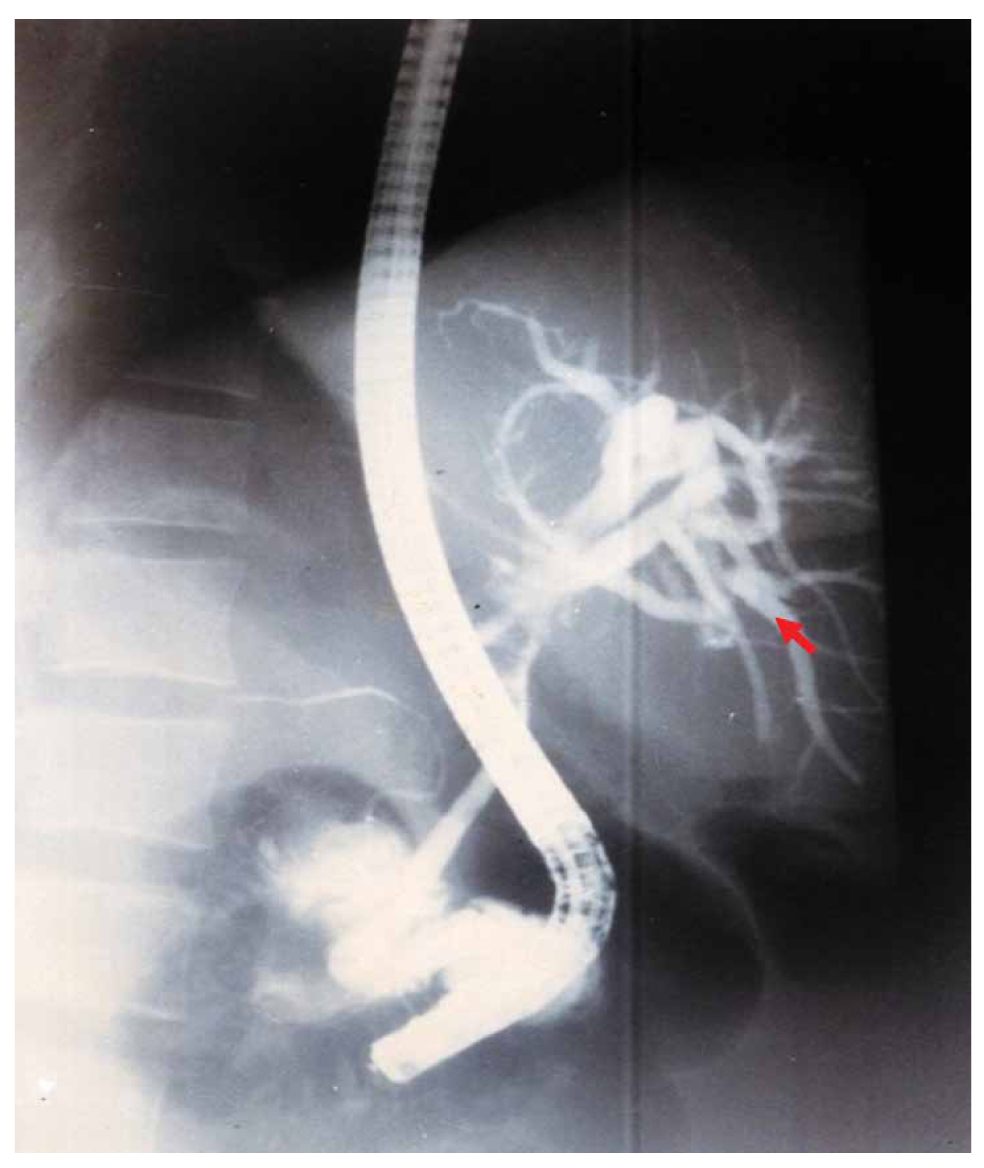

Three patients developed CSC at 2, 3, and 7 months postoperatively (Table 1). The diagnosis was established based on the following criteria: (i) a history of previous surgery for LHC with documented intracystic injection of scolicidal agents; (ii) early postoperative onset of progressive obstructive jaundice; (iii) normal biliary tract appearance during the initial surgery and on intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), excluding preexisting bile duct narrowing; (iv) cholangiographic evidence (ERCP or percutaneous cholangiography) of new multifocal or segmental biliary strictures consistent with sclerosing cholangitis (Figure 1); and (v) exclusion of other potential causes such as iatrogenic bile duct injury (no intraoperative injury identified), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) (no diffuse inflammatory involvement or extrahepatic association), and neoplastic strictures (no mass lesion on imaging or histology). These criteria are consistent with those described by Belghiti et al. and subsequent reports.

Figure 1. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showing stenosis of the bile duct convergence (arrow).

In all 3 cases, CSC evolved insidiously, progressing to SBC characterised by chronic cholestasis, portal hypertension, and recurrent cholangitis. The disease followed a relentless course, with fatal outcomes in all patients between 2 and 6 years postoperatively, despite repeated biliary drainage and supportive management. None were successfully evaluated for liver transplantation due to rapid progression and associated comorbidities.

Clinical discussion

Caustic sclerosing cholangitis (CSC), as termed by Belghiti et al. [3], is a rare form of secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC), less commonly seen in clinical practice. Unlike primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), CSC progresses rapidly, and its prognosis is more unfavorable. It is localised to only a part of the biliary tree, unlike PSC where the entire tree is affected [6].

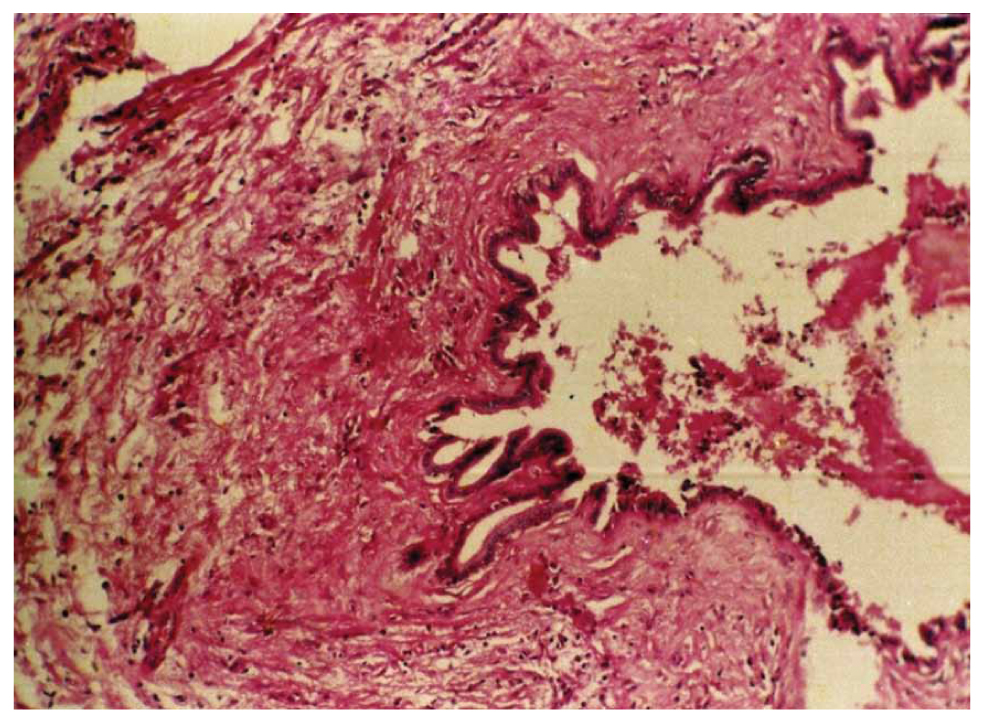

Various experimental studies have examined the effects of 95% alcohol, 10% povidone iodine, 0.9% – 5% – 10% – 20% NaCl, 3% H2O2, 5% formalin, 0.5% silver nitrate, and cetrimide on the liver and biliary tree. Serious hepatobiliary complications have been reported for formalin, alcohol, and 10%-20% NaCl [7,8]. K. W. Warren et al. [9] reported in 1966 in their study of 42 cases of sclerosing cholangitis the first case of CSC. The pathogenic effect of scolicidal products on the biliary mucosa is now well-known experimentally; indeed, in all reported cases, a CBF was present, allowing the passage of scolicidal solution into the bile duct tract, thus exposing the mucosa to chemical aggression. In all reported cases, the bile duct tract was normal at the time of primary surgery; sclerosing lesions developed rapidly afterward, affecting both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. In the present study, the 3 observed cases of CSC were presented with direct injection into the cyst after aspiration of 20 to 30 cc of hydatid fluid corresponding to the volume of scolicidal solution injected. Absence of bile duct lesions was observed, and cholangitis lesions developed rapidly without infectious episodes (Figure 2). In most reported cases, 2% formalin solution was the incriminated scolicidal solution in the development of sclerotic lesions. However, hypertonic solutions may also be responsible for CSC.

Figure 2. Microscopic view of a liver biopsy showing features of sclerosing cholangitis.

Houry et al. [10] demonstrated in their experimental study that direct injection of 20% hypertonic saline solution and 0.5% formaldehyde solution into the biliary tree induced histopathological changes in the biliary tree epithelium, including focal hepatocyte necrosis, sinusoidal flattening, Kupffer cell hyperplasia, regenerative changes in hepatocytes, fibroblastic proliferation, and necrosis in the extrahepatic bile ducts [11]. These lesions were interpreted as an early stage of CSC. 2% formaldehyde solution, corresponding to the concentration used to sterilise human hydatid cysts, caused sclerosing cholangitis in most rats and pseudocirrhosis in some of them 3 months after injection into the biliary tree [10]. Caustic damage to the epithelium of the communicating bile ducts has also been reported when using silver nitrate as a scolicidal agent [12]. The pathogenesis of these lesions remains speculative. The lesions could be due to infectious, vascular, chemical, or immunological factors; this could explain their late development and, in some cases, their development in areas distant from those presumed to be directly exposed to formaldehyde solution [13]. After evaluating the side effects on the hepatobiliary system and in vivo activity, Kilicoglu et al. [14] concluded in their experimental study that 10% diluted honey could be used as a potential scolicidal agent.

Several fundamental factors are thought to contribute to the development of CSC [11,15]. The disease arises when a scolicidal agent is injected into the cyst cavity in the presence of a cysto-biliary communication, allowing the solution to enter the biliary tract. Prolonged exposure of the bile ducts to the scolicidal agent further aggravates the chemical injury, and individual sensitivity to the agent may amplify tissue damage once contact occurs.

The key diagnostic points of CSC have been well described in the literature [3,16]. A typical history involves previous surgery for LHCs with the use of chemical agents aimed at destroying the scolex or damaging the cyst wall. Importantly, the bile ducts usually appear normal before and during the operation, and the subsequent development of lesions is related to the presence of a cysto-biliary communication, to adhesions, or to a new communication that appears after excision of the cyst. Clinically, patients present with recurrent episodes of biliary obstruction and infection, most often characterised by obstructive jaundice at an early stage, which may progress to a mixed form in advanced disease. Imaging, particularly MRCP, typically reveals localised bile duct stenosis with dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts, although distal bile duct stenosis is rare. Liver function is frequently impaired, often reaching Child-Pugh class B or C. Histopathological evaluation of bile duct biopsies generally demonstrates a chronic inflammatory reaction. Finally, the diagnosis requires careful exclusion of other causes of obstructive biliary disease, such as PSC, iatrogenic BDI, or neoplastic strictures.

Symptoms of CSC are similar to those of PSC and manifest as progressive jaundice, which is often confused with iatrogenic biliary trauma and biliary obstruction caused by scolex fragments, with a rapidly increasing GGT level within seven days, followed by a progressive increase in BT and PAL levels. Ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), or endoscopic US may show suggestive anomalies and allow the exclusion of other causes of cholestatic jaundice. However, the normality of these examinations does not exclude the diagnosis of CSC. The reference examination is direct bile duct opacification, by transhepatic puncture or preferably by ERCP. Anatomically, several patterns of lesions have been described in CSC. One common feature is the alternation of stenotic and dilated zones, producing a characteristic mound-like appearance. In other cases, diffuse segmental stenoses are observed, or alternating stenoses with non-stenotic peripheral segments. The involvement of peripheral bile ducts may result in a marked reduction of bile tree branching, creating the so-called “dead tree” appearance. In addition, a stenotic narrowing at the level of the main bile duct can be associated with sacculated or ampullary dilatation of the proximal intrahepatic bile ducts.

A classification of stages of increasing severity is schematised by Li-Yeng and Goldberg [17]. The main goal of treatment is to relieve biliary obstruction, alleviate symptoms, and improve survival and quality of life for these patients. Medical treatment includes long-term use of ursodeoxycholic acid, which eliminates endogenous bile acids and protects hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells. Concurrent use of ursodeoxycholic acid during biliary obstruction relief may accelerate cholestasis regression [18]. Corticosteroids and immunosuppressants are often used to reduce jaundice, owing to their anti-inflammatory and immunological properties, allowing tissue damage reduction.

Sezer et al. [19] suggested that melatonin may effectively improve the prognosis of patients with CSC, but this still requires clinical confirmation. In case of angiocholitis, medical treatment is limited to antibiotic therapy and parenteral administration of vitamin K. ERCP is an effective means of improving biliary stasis, offering significant benefits in terms of therapeutic efficacy and low adverse effects. Biliary stent placement, in particular, can effectively restore enterohepatic bile circulation, often constituting the main treatment for CSC [20]. Cameron and Gayler [21] proposed resection of the extrahepatic bile duct up to the intrahepatic bile duct convergence where stenosis is predominant and performing bilioenteric anastomosis on a Y-loop.

All these strategies aim to relieve symptoms in a palliative manner but have no impact on CSC progression. Morali [22] reported a case of a 16-year-old girl operated on for a LHC using 2% formaldehyde. She developed CSC immediately postoperatively, treated with ERCP and antibiotic therapy, and after a year she developed SSC, then she ended up being transplanted after 4 years. Liver transplantation remains the only potential cure, but its implementation must strictly adhere to indications.

The prognosis of CSC is severe due to rapid progression to PSC and portal hypertension syndrome as well as associated complications [3]. Death occurs within less than 5 years after the first clinical signs in the absence of liver transplantation [3,23]. Importantly, contemporary WHO and experts now places greater emphasis on prevention of spillage and protection of the surgical cavity, and does not mandate intracystic injection of scolicidal solutions; perioperative benzimidazole therapy (e.g., albendazole) and meticulous surgical techniques to avoid cysto-biliary contamination are recommended as safer strategies. Given the balance between potential benefits and the proven risk of BDI, many centers now avoid intracystic injection altogether, preferring containment with antiparasitic therapy or non-injectable topical methods when sterilisation is required [24]. These more conservative, guideline-informed approaches aim to minimise the rare but catastrophic complication of CSC while still addressing the parasitic risk [25].

Our study adds to the existing literature by providing one of the few documented case series of CSC following surgical treatment of LHCs. Unlike previous reports that have often described isolated cases, our work highlights 3 fatal outcomes within a well-defined surgical cohort, thereby illustrating the frequency, clinical course, and lethality of this complication in an endemic setting. By situating these cases within a retrospective series of 268 operated patients, we emphasise not only the direct link between scolicidal agent use and subsequent biliary injury but also the importance of contemporary surgical practice, which now discourages intracystic instillation of caustic solutions. Furthermore, we underline the lack of effective curative treatment short of liver transplantation, thereby stressing the critical need for prevention. This case series thus provides practical insights into diagnosis, follow-up, and prevention strategies, complementing previous isolated case descriptions and reinforcing current guideline recommendations against the use of scolicidal agents.

Conclusion

The occurrence of caustic sclerosing cholangitis (CSC) underscores the serious risks associated with the intracystic injection of scolicidal solutions during liver hydatid cyst (LHC) surgery. The practice of injecting formalin or other caustic agents into the cyst cavity has no proven benefit in preventing intraperitoneal dissemination and carries a significant potential for irreversible biliary injury when a cysto-biliary communication is present. Accordingly, this technique has been completely abandoned in our current surgical practice.

Prevention remains the cornerstone of management. Strict adherence to safe surgical principles meticulous isolation of the operative field, careful management of any cysto-biliary communication, and avoidance of intracystic injection is essential. When sterilisation of the cyst cavity is required, gentle mechanical evacuation and cleansing of the endocyst using compresses soaked in a diluted scolicidal solution under continuous suction provide effective local control while minimising risk. Perioperative benzimidazole therapy and compliance with WHO-endorsed treatment strategies further reduce recurrence and ensure patient safety.

These findings highlight a critical clinical message: the prevention of CSC depends on eliminating the use of caustic intracystic agents and adopting modern, conservative, and evidence-based techniques for hydatid cyst management.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from the General Surgery Department of Ibn Sina University Hospital Ethics Committee.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Registration of Research

N/A.

Clinical trial number

N/A.

References

- Denzinger M, Nasir N, Steinkraus K, Michalski C, Hüttner FJ, Traub B. Therapiekonzepte bei hepatischer Echinokokkose [Treatment concepts for hepatic echinococcosis]. Chirurgie (Heidelb). 2023 Jun;94(6):560-70. German. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00104-023-01825-w. Doi: 10.1007/s00104-023-01825-w.

- Pissiotis CA, Wander JV, Condon RE. Surgical treatment of hydatid disease: Prevention of complications and recurrences. Arch Surg. 1972 Apr;104(4):454-9. Doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180040068012.

- Belghiti J, Benhamou JP, Houry S, Grenier P, Huguier M, Fékété F. Caustic sclerosing cholangitis. A complication of the surgical treatment of hydatid disease of the liver. Arch Surg. 1986 Oct;121(10):1162-5. Doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400100070014.

- Bories P, Mirouze D, Aubin JP, Pomier-Layrargues G, Monges A, Miniconi P, et al. Sclerosing cholangitis following surgical treatment of hydatid cysts of the liver. Probable role of the formol injection of bile ducts. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1985 Feb;9(2):113-6

- Venkatesh M, Knipe H, Bell D, et al. WHO-IWGE classification of cystic echinococcosis. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org [Accessed on 03 May 2025]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-26148.

- Azizi L, Raynal M, Cazejust J, Ruiz A, Menu Y, Arrivé L. MR imaging of sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012 Apr;36(2):130-8. Doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.11.011

- Yetim I, Erzurumlu K, Hokelek M, Baris S, Dervisoglu A, Polat C, et al. Results of alcohol and albendazole injections in hepatic hydatidosis: Experimental study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Sep;20(9):1442-7. Doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03843.x.

- Topcu O, Aydin C, Arici S, Duman M, Sen M, Koyuncu A. The effects of various scolicidal agents on the hepatopancreatic biliary system. Chir Gastroenterol. 2006 Sep;22:185-90.

- Warren KW, Athanassiades S, Monge JI. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. A study of forty-two cases. Am J Surg. 1966 Jan;111(1):23-38. Doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(66)90339-4.

- Houry S, Languille O, Huguier M, Benhamou JP, Belghiti J, Msika S. Sclerosing cholangitis induced by formaldehyde solution injected into the biliary tree of rats. Arch Surg. 1990 Aug;125(8):1059-61. Doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410200123020

- Sahin M, Eryilmaz R, Bulbuloglu E. The effect of scolicidal agents on liver and biliary tree (experimental study). J Invest Surg. 2004 Nov-Dec;17(6):323-6. Doi: 10.1080/08941930490524363.

- Behrns KE, van Heerden JA. Surgical management of hepatic hydatid disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991 Dec;66(12): 1193-7. Doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62469-0.

- Terés J, Gomez-Moli J, Bruguera M, Visa J, Bordas JM, Pera C. Sclerosing cholangitis after surgical treatment of hepatic echinococcal cysts. Report of three cases. Am J Surg. 1984 Nov;148(5):694-7. Doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90353-2.

- Kilicoglu B, Kismet K, Kilicoglu SS, Erel S, Gencay O, Sorkun K, et al. Effets du miel en tant qu’agent scolicide sur le système hépatobiliaire. World J Gastroenterol 2008 Apr; 14(13): 2085-8. Doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2085

- Faïk M, Oudanane M, Halhal A, Housni K, Ahalat M, Baroudi S, et al. Cholangite sclérosante caustique: À propos d’un cas. Médecine du Maghreb [Internet]. 1998 n°69. Available from: https://www.santetropicale.com/Resume/6902.pdf

- Liu Yu, Liu Su. Current research status on the diagnosis and treatment of secondary sclerosing cholangitis. International Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2013;33(3): 182-5.

- Li-Yeng C, Godberg HI. Sclerosing cholangitis: Broad spectrum of radiographic features. Gastro-intest. Radiol. 1984;9:39-47. Doi: 10.1007/BF01887799

- Mai Qiaoxun. Efficacy analysis of ursodeoxycholic acid combined with ERCP in the treatment of obstructive jaundice. Chinese Practical Medicine. 2020;15(21):127-9.

- Sezer A, Hatipoglu AR, Usta U, Altun G, Sut N. Effects of intraperitonealmel- atonin on caustic sclerosing cholangitis due to scolicidal solution in a rat model. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2010 Apr;71(2):118-28. Doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2010.03.004

- Jang S, Lee DK. Update on pancreatobiliary stents: Stent placement in advanced hilar tumors. ClinEndosc. 2015 May;48(3):201-8. Doi: 10.5946/ce.2015.48.3.201

- Cameron JL, Gayler BW, Herlong HF, Maddrey WC. Sclerosing cholangitis: Biliary reconstruction with Silastictranshepatic stents. Surgery. 1983 Aug;94(2):324-30.

- Morali G, Safadi R, Pappo O, Jurim O, Shouval D. Caustic sclerosing cholangitis treated with orthotopic liver transplantation. IMAJ 2002;4:1152-3.

- Cohen-Solal JL, Eroukhmanoff P, Desoutier P, Loisel JC, Kohlmann G, Flabeau F. Cholangite sclérosante survenue après traitement d’un kyste hydatique du foie. Sem Hôp Paris. 1983;21:1623-24.

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for the treatment of patients with cystic echinococcosis (2025) [Internet]. Emphasizes prevention of spillage and use of non-invasive/medical options where appropriate. (WHO guideline document). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240110472

- Besim H, Karayalçin K, Hamamci O, Güngör C, Korkmaz A. Scolicidal agents in hydatid cyst surgery. HPB Surg. 1998;10(6):347-51. Doi: 10.1155/1998/78170.