Original Article

Hell J Surg. 2025 Jan-Mar;95(1):5–16

doi: 10.59869/25054

Magdalini Kaprianou, Orestis Ioannidis, Elissavet Anestiadou, Eleni Salta-Poupnara, Freiderikos Tserkezidis, Savvas Symeonidis, Stefanos Bitsianis, Konstatntinos Angelopoulos, Stamatios Angelopoulos

Fourth Department of Surgery, “Georgios Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Exochi, Greece

Correspondence: Elissavet Anestiadou, MD, MSc, PhDc, Fourth Department of Surgery, General Hospital “George Papanikolaou”, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Exochi, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece, e-mail: elissavetxatz@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: The intention to leave the profession among nurses often arises from dissatisfaction or a lack of professional fulfillment. The departure of nurse anaesthetists has significant implications for healthcare delivery, as their role in anaesthesia and perioperative care is both specialised and indispensable. The process of replacing nurse anaesthetists is time-intensive, requiring extensive training and adaptation to new working environments.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 194 Greek nurse anaesthetists working in public hospitals in Greece to examine factors influencing turnover intentions. A total of 111 completed questionnaires were collected using a structured tool that assessed demographics, job satisfaction, perceived stress, and intention to leave. The study assessed work-related stress, work-family conflict, psychological empowerment, organisational commitment, work commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions using a structured questionnaire.

Results: A total of 111 anaesthesia nurses participated in the study. The results revealed that high levels of perceived stress and low job satisfaction were significantly associated with increased intention to leave the current position (p < 0.05). Additionally, work–family conflict was found to be a strong predictor of turnover intention (p < 0.05), particularly among participants with caregiving responsibilities. Statistically significant associations were also observed between intention to leave and variables such as age, years of experience, and type of employment. Nurses with fewer years in the profession and those in temporary contracts were more likely to consider leaving. These findings highlight the multidimensional nature of turnover intention, shaped by both occupational stressors and personal circumstances.Conclusions: In contrast to prevailing theoretical frameworks, nurse anaesthetists’ turnover intentions appear to be unaffected by work-related stress and work-family conflict. Instead, psychological empowerment and organisational commitment serve as primary determinants of retention. Although job satisfaction does not directly influence nurses’ intention to leave the profession, it may contribute to decisions regarding workplace transitions within the healthcare sector.

Key Words: Turnover intention, organisational commitment, nurse anaesthetists, job satisfaction, work-family conflict

Submission: 02.02.2025, Acceptance: 05.05.2025

Introduction

The term “intention to leave” in the literature refers to an individual’s consideration of voluntarily changing their department or workplace [1]. For anaesthesia nurses, this decision is particularly critical, not only for their own professional trajectory but also for the department they serve. Their role within the anaesthesiology ward is pivotal and irreplaceable in ensuring high-quality patient care [2]. Retention in the profession is influenced by multiple factors, including professional fulfillment [3], commitment to the organisation, and overall job satisfaction.

Several additional factors contribute to nurses’ turnover intentions, including economic considerations related to salary and employment conditions, workplace conflicts, understaffing, and increasing job demands that may conflict with long-term career stability [4]. Despite the global recognition of nursing shortages and the widespread concern regarding nurses’ intentions to leave [5], efforts to enhance job satisfaction alone have not yielded significant improvements in retention [2].

A seminal study by Mobley et al. [6], which examined 203 hospital professionals across various specialties, concluded that an individual’s intent to leave is often a precursor to permanent departure. Research has also indicated no significant correlation between age and retention in the nursing profession [7–11]. Furthermore, Mobley, Horner, and Hollingsworth [6] suggested that once a nurse begins contemplating resignation, they actively seek alternative career opportunities. One of the key indicators of turnover intention is dissatisfaction with the work environment [12]. High dissatisfaction levels are often associated with a poor workplace atmosphere, which can lead to professional disengagement and eventual departure [13]. However, research addressing the definitive and long-term departure of nurses from the profession remains limited [14].

According to data from the 2018 U.S. National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses [15], approximately 13.6% of nurse anaesthetists left their positions within a single year, while an additional 37.6% considered leaving but did not resign, bringing the total proportion affected by turnover intent to over 50% [15]. The most frequently cited reason for this trend was “better pay and benefits,” surpassing even burnout as a motivating factor. While comparable national data for Greece are lacking, similar concerns have been raised in local healthcare settings. Nurses in Greece face comparatively lower salaries than their European counterparts, compounded by a rising cost of living, which likely contributes to dissatisfaction and attrition. These pressures underscore the importance of investigating the factors influencing anaesthesia nurses’ decisions to stay or leave their roles.

Recent literature has also highlighted the complexity of nurses’ turnover intentions, distinguishing between intention to leave the current workplace and intention to leave the profession entirely. Decision to leave is not solely determined by job dissatisfaction, but also by lack of recognition, personal strain, and limited professional development opportunities [15]. In addition, there is conceptual differentiation between organisational and professional withdrawal, as some nurses may seek to transfer within the system, while others may consider a full exit from nursing. These two constructs—intention to leave the organisation and intention to leave the profession—are interconnected but distinct, and their separate evaluation provides a deeper understanding of the underlying motivations behind turnover in specialised nursing roles [16].

This study aims to investigate the factors influencing anaesthesia nurses’ intentions to leave their profession and how these factors impact their decision-making process. By identifying the primary drivers behind turnover intentions, this research seeks to provide insights into the potential weakening of the nursing sector, particularly in the field of anaesthesiology [17].

Material and Methods

To examine the factors influencing nurse anaesthetists’ turnover intentions, the following hypotheses were investigated for their correlation with turnover:

i. Work-related stress and intention to leave.

ii.Work-family conflict and intention to leave.

iii. Organisational commitment and intention to leave.

iv. Work commitment and intention to leave.

v. Psychological empowerment and intention to leave.

vi. Job satisfaction and intention to leave.

Study Design and Data Collection

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among nurse anaesthetists working in 15 Greek hospitals under the jurisdiction of the 3rd and 4th Regional Health Authorities (YPE) in Central Macedonia. Approval was obtained from the respective scientific councils of the YPEs and the hospitals. The survey was distributed between March and May 2022, either in person or by post, with additional copies sent to hospitals that requested them. Out of the 194 questionnaires distributed, 111 were completed and returned.

Demographic and Professional Characteristics

The first section of the questionnaire collected demographic and professional data, including:

- Personal Information: Gender, age, marital status, and educational background.

- Professional Data: Employment status, organisational structure, role within the anaesthesiology department, number of operating rooms, availability of recovery units, presence of a nurse in each operating theater, and total years of experience in both nursing and anaesthesiology.

- Family-related Data: Marital status and its potential impact on work-family balance.

This demographic profiling aimed to assess how experience, specialisation, and personal circumstances influenced turnover intentions.

Survey Instrument

The questionnaire consisted of seven units, including in total 63 items, designed to assess work-related stress, work-family conflict, organisational and work commitment, job satisfaction, psychological empowerment, and turnover intentions (Supplementary Material 1). Responses were coded using various Likert scales to quantify levels of agreement or frequency, allowing for the creation of composite scores for each variable.

The response scales were structured as follows:

- Emotional State Questions: 0–4 (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree)

- Family State Questions: 1–7 (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree)

- Work State Questions: 0–6 (Never to Very Often)

- Work Environment Questions: 1–5 (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree)

Measurement Scales

The following questions related to the investigation of the examined variables were derived from validated bibliographic sources, with responses provided on a Likert scale, to measure key variables:

The «Work-Related Stress and intention to leave « section was developed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire [18], and consists of ten items assessing subjective stress perception. A total score ranging from 0–13 indicates low stress levels, 14–26 represents moderate stress perception, and 27–40 reflects high stress levels. For items 4, 5, 7, and 8, reverse scoring was applied, with values adjusted as follows: 0 = 4, 1 = 3, 2 = 2, 3 = 1, and 4 = 0.

The «Work-Family Conflict and intention to leave « section was based on the Work and Family Conflict Scale (WAFCS) questionnaire [19], which comprises ten statements. Each respondent’s total score is calculated, with higher scores indicating greater levels of work-family conflict.

The “Work Commitment and intention to leave “ section utilised the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) [20], a nine-item measure of employee engagement and commitment. The cumulative score of each respondent is used to measure work commitment, where higher scores reflect a stronger commitment to work.

The “Psychological Empowerment and intention to leave “ section, measured using a 12-item scale adapted from Spreitzer’s Psychological Empowerment Questionnaire [21], assessed the psychological empowerment nurses experience in their work. Higher scores on this variable denote greater psychological empowerment.

The “Organisational Commitment and intention to leave”, measured using a 9-item scale [22] that assesses employees’ attachment to their organisation section, explored the commitment employees feel toward the hospital in which they work. Responses were summed to create the organisational commitment variable. Due to the wording of question 2, reverse scoring was applied. High cumulative scores on this variable indicate low commitment to the organisation.

The “Job Satisfaction and intention to leave” section, assessed using a validated nine-item scale [23], focused on the level of satisfaction nurses feel within their department. Responses were summed to calculate the total job satisfaction score, with higher scores indicating greater job satisfaction.

For the “Intention to Leave the Organisation” section, responses were summed to create a total variable score. Due to the wording of question 3, reverse scoring was applied. High scores indicate a greater intention to leave the organisation.

Finally, the “Intention to Leave the Profession” section included a single direct question where nurses were asked to respond honestly regarding their intention to leave the profession.

Statistical Analysis

The questionnaire responses were analysed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) to examine the relationships between selected variables and the intention to leave. This method is suitable for handling multiple factors with a high number of related questions. The following hypotheses were tested: whether work-related stress, job satisfaction, work-family conflict, organisational commitment, psychological empowerment, and work engagement influence nurses’ intention to leave their current position or profession.

Spearman’s correlation coefficient values range from -1 to 1, where positive values indicate a direct relationship and negative values indicate an inverse relationship. After calculating the correlation coefficient for each variable, hypothesis testing was conducted to determine whether the coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Survey Instrument

To ensure internal consistency of the measurement instruments used, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for each questionnaire section. All scales demonstrated acceptable to excellent reliability. Specifically, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84, indicating good reliability. The Work–Family Conflict Scale (WAFCS) had a reliability coefficient of 0.87. The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) yielded an alpha of 0.92, and the Psychological Empowerment Scale showed a value of 0.89. For the Organisational Commitment Scale, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81, while the Job Satisfaction Scale achieved 0.85. Lastly, the Turnover Intention Scale had an internal consistency coefficient of 0.83. These values confirm the reliability of the instruments in assessing the intended psychosocial constructs.

Results

Sample Data Collection

Data for this study were collected using a structured questionnaire distributed to anaesthesia nurses working in 15 Greek hospitals under the jurisdiction of the third and fourth Regional Health Authorities (YPE) in Central Macedonia. Approval was obtained from the relevant scientific councils, and the survey was conducted between March and May 2022. The questionnaires were distributed either in person or by post, with additional copies sent to hospitals upon request. A total of 194 questionnaires were distributed, and 111 completed responses were received and analysed. The questionnaire included sections on demographic and professional characteristics. Participants provided information on gender, age, marital status, and education level. Work-related data were also collected, including employment status, work organisation, position within the anaesthesiology department, number of operating rooms, availability of a recovery unit, and whether a nurse was assigned to each operating room. Additionally, participants reported their total years of experience in both nursing and anaesthesiology. Given the potential impact of work-family balance on turnover intentions, marital status was also recorded.

Demographics and Background Information

The final sample consisted of 16 male nurses (14.4%) and 95 female nurses (85.6%), with an average age of 46.9 years (median 48 years, SD ± 7.8 years). Of the respondents, 68% reported being married, followed by 14% who were single, 10% who were divorced, and 5% who were in a relationship. The lowest percentages were observed among widowed individuals and those in a civil partnership, each accounting for 2% of the sample. Regarding educational background, the majority (89%) of respondents had obtained higher education degrees in nursing, while 11% had secondary education qualifications. Among the higher education graduates, 62% had graduated from Technological Educational Institutes (TEI), 2% from universities (AEI), and 25% held postgraduate degrees, emphasising the importance of further professional development in nursing. In terms of employment status, 89.2% of the participants were permanent public sector employees, while the remaining 10.8% were on fixed-term contracts. The nursing staff primarily consisted of operating room nurses (84.7%), with supervisors and deputy supervisors comprising 15.3%. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Work Experience

The average work experience in nursing was 22.5 years (median 23 years), with a standard deviation of 8.67 years. The least experienced nurse had one year of service, while the most experienced had 38 years, resulting in a range of 37 years. In the anaesthesiology department, work experience ranged from a minimum of one year to a maximum of 34 years, with a mean of 8.76 years (median 6 years) and a standard deviation of 7.65 years, leading to a range of 33 years.

Operating Room Statistics, Workplace Resources and Staffing

The average number of operating rooms reported was 7.27 (median 5), with a standard deviation of 4.95. The minimum number of operating rooms was one, and the maximum was 21, resulting in a range of 20. Additionally, 84.7% of the respondents indicated that their hospital included a recovery area on-site, while 79.3% stated that there was one nurse assigned to each operating room. Additional workplace-related information, including recovery unit availability and nurse allocation per operating room, is summarised in Table 2.

Correlation analysis of key variables

The descriptive statistics for the aggregated variables are presented in Table 1. More particularly:

- Work-Related Stress: There was no significant correlation between work-related stress and the intention to leave (ρ = 0.106, p = 0.271).

- Work-Family Conflict: Similarly, no significant relationship was found between work-family conflict and the intention to leave (ρ = 0.139, p = 0.150).

- Job Satisfaction: No significant correlation was observed between job satisfaction and the intention to leave (ρ = 0.129, p = 0.176).

- Work Engagement: A moderate negative correlation was found between work engagement and the intention to leave (ρ = -0.384, p < 0.001).

- Psychological Empowerment: Psychological empowerment showed a strong negative correlation with the intention to leave (ρ = -0.511, p < 0.001).

- Organisational Commitment: A strong negative correlation was observed between organisational commitment and the intention to leave (ρ = -0.479, p < 0.001).

Significant variables and their influence

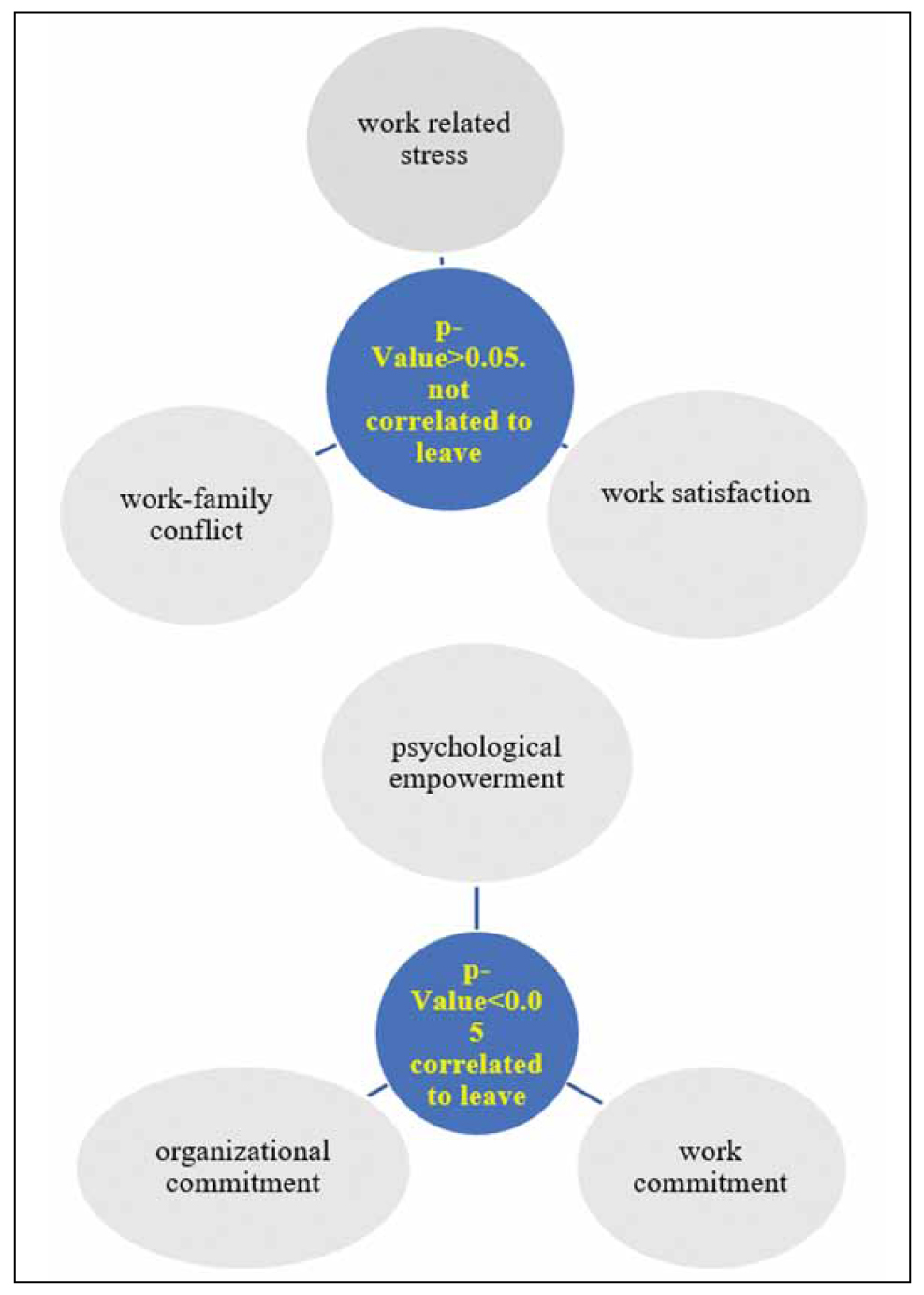

Only work engagement (p < 0.001), psychological empowerment (p < 0.001), and organisational commitment (p < 0.001) were significantly correlated with the intention to leave. These variables demonstrated a moderate to strong negative relationship, indicating that higher levels of these factors were associated with a reduced likelihood of leaving. Conversely, work-related stress, work-family conflict, and job satisfaction were not significantly associated with the intention to leave (p > 0.05). Detailed results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1. In addition, Table 4 presents the significant and non-significant variables alongside their correlation coefficients and p-values.

Figure 1. Correlation and grouping of variables.

Additional Findings

The mean score for intention to leave the profession was 2.05 (median: 2, SD: 1.29), highlighting low overall turnover intentions among the surveyed nurses.

Discussion

The present study explored factors influencing turnover intention among anaesthesia nurses in Greece, focusing on work-related stress, work–family conflict, psychological empowerment, organisational commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction. Contrary to widespread theoretical assumptions, the findings revealed that neither work-related stress nor work–family conflict significantly influenced turnover intentions in our sample. This is noteworthy, as previous research has consistently identified stress and work–family imbalance as significant predictors of turnover in nursing populations [24,25]. A plausible explanation for this divergence is the high level of professional resilience and adaptation exhibited by anaesthesia nurses, who may have developed coping mechanisms due to the critical nature of their role [26].

Nurses’ intention to leave does not appear to be significantly influenced by work-related stress. This finding contradicts the initial hypothesis, as stress is often cited as a major factor influencing turnover intentions in other professions. It is possible that nurse anaesthetists have adapted to the unique and intense stressors of their roles, which mitigates its impact on their career decisions.

Similarly, the findings suggest that work-family conflict does not significantly affect nurse anaesthetists’ intention to leave. This result challenges existing theories, which posit that neglecting family needs or encountering challenging family circumstances increases turnover intentions. A plausible explanation is that the specialised nature of the profession and the expertise of nurse anaesthetists foster a sense of duty that families may come to understand and tolerate.

Psychological empowerment emerged as a robust predictor of retention. Nurses who reported feeling autonomous, competent, and impactful in their roles were significantly less likely to consider leaving [27,28]. This aligns with findings by Fragkos et al. [29] and Ibrahem et al. [30], who emphasised that psychological empowerment fosters professional engagement and reduces turnover intent. Empowered nurses often perceive greater control over their work environment, which enhances job satisfaction and organisational loyalty [31].

Similarly, organisational commitment demonstrated a strong negative association with turnover intention. This supports Meyer and Allen’s [32] three-component model of commitment, wherein affective commitment—emotional attachment to the organisation—is inversely related to turnover intent. Nurses with a strong sense of belonging and alignment with organisational values are more likely to remain in their positions, consistent with findings from Park and Kim [33] in healthcare settings. The above are consistent with theories by Reichheld and Team [34] and Kyle LaMalfa [35], the results indicate that a greater sense of belonging within an organisation reduces nurses’ intention to leave. Conversely, a lack of organisational commitment serves as a strong predictor of turnover [27].

The current findings align with previous research suggesting that intention to leave the organisation does not necessarily equate to intention to abandon the profession [36]. Literature supports that some nurses contemplate internal mobility due to unfavorable conditions in their current workplace, while maintaining a commitment to their professional identity [37]. This distinction is crucial for developing retention strategies, as it highlights the need for targeted interventions at both the organisational and systemic levels. Understanding whether nurses are seeking change within their field or contemplating complete professional exit allows for mor

Interestingly, job satisfaction did not exhibit a significant effect on turnover intentions in our study. This contrasts with seminal work by Mobley et al. [6], who identified job dissatisfaction as a primary driver of employee turnover. One potential reason for this discrepancy could be that job satisfaction, while important, does not fully capture the complexities of professional identity and commitment in highly specialised roles such as anaesthesia nursing. Recent literature suggests that intrinsic motivators, such as perceived professional growth and recognition, might weigh more heavily than general job satisfaction in influencing turnover decisions [38].

In conclusion, this study advances our understanding of turnover intentions among anaesthesia nurses by highlighting the protective roles of psychological empowerment, organisational commitment, and work engagement. Interventions targeting these factors could play a pivotal role in retaining skilled anaesthesia nurses, ultimately safeguarding the quality of patient care in surgical settings.

Practical implications

The role of a nurse anaesthetist is demanding and specialised, encompassing responsibilities such as managing emergencies, administering anaesthesia, and interpreting patients’ vital signs. The stress inherent in this role is intensified by frequent technological advancements, staff shortages, and the perception by hospital administrations that anaesthesiology is an “easier” department. These challenges, compounded by minimal recognition, insufficient training, and outdated working conditions, contribute to turnover intentions.

To address these issues, several measures can be implemented. Continuous professional development, recruitment of younger staff, and incentives such as participation in conferences and educational programs are critical. Establishing anaesthesia nursing as a formal specialty in Greece, accompanied by structured training and certification, could enhance the profession’s prestige and improve retention rates. Flexible working hours and childcare support could also alleviate work-life conflicts, enabling nurse anaesthetists to focus on their demanding roles.

Limitations

This study is limited by its relatively small sample size, which may not adequately capture the diverse experiences of anaesthesiology nurses and, while adequate for exploratory analysis, limits generalizability. Additionally, selection bias may have influenced the results, as dissatisfied nurses may have been more inclined to respond. Logistical challenges, including delays in questionnaire distribution and geographical barriers, further constrained the study.

Furthermore, while the findings highlight important work-related and psychosocial factors influencing turnover intention, the economic aspect was not directly assessed in our questionnaire. Nevertheless, financial stress due to low salaries and high living expenses is likely to affect job satisfaction and long-term career decisions. Economic factors, such as salary dissatisfaction—a well-documented driver of nurse turnover [39]-were not explicitly assessed in this study but likely play a role. This omission represents a noteworthy limitation and an area for future research. Furthermore, the study sample had a high average length of work experience (22.5 years), which may reflect a population less inclined to change professions. Finally, the focus on anaesthesia nurses, while relevant to the scope of the study, excludes other nursing specialties that may face different stressors, such as more frequent or intense shift work. Future studies should aim to include a wider range of departments to examine broader patterns of work-related stress and turnover intent across nursing populations. In addition, including younger nurses in future studies would likely yield a broader and more dynamic range of perspectives, while utilisation of electronic distribution methods could yield a larger and more representative sample.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing nurse anaesthetists’ intention to leave their roles. Expanding the scope of future research to include more anaesthesiology departments across Greece could offer a more comprehensive understanding of these determinants. Such efforts will guide the development of targeted strategies to address turnover intentions and improve workforce stability in this critical field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- O’Brien-Pallas L, Griffin P, Shamian J, Buchan J, Duffield C, Hughes F, Spence Laschinger HK, North N, Stone PW. The Impact of Nurse Turnover on Patient, Nurse, and System Outcomes: A Pilot Study and Focus for a Multicenter International Study. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2006 Aug;7(3):169-79.

- Miltiadis C, Lappa E. Investigation of incentives to reduce the intention of nurses to leave in a period of economic crisis. Arch Ell Iatro. 2021 Mar-Apr;38(2):261-7.

- Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J Vocat Behav. 2009 Jun;74(3):235-44. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.003

- Spanou V. The mobility of employees at Papageorgiou General Hospital in Thessaloniki. Various causes of withdrawal and association with burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, personal achievement).” Diploma thesis [Internet]. University of Macedonia. 2014. Available from: https://dspace.lib.uom.gr/bitstream/2159/15982/6/SpanouVasilikiMsc2014.pdf

- Holtom BC, Mitchell TR, Lee TW, Eberly MB. 5 Turnover and Retention Research: A Glance at the Past, a Closer Review of the Present, and a Venture into the Future. Academy of Management Annals [Internet]. 2008;2(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19416520802211552 Doi:10.1080/19416520802211552.

- Mobley WH, Horner SO, Hollingsworth AT. An evaluation of precursors of hospital employee turnover. J Appl Psychol. 1978 Aug;63(4):408-14.

- La Rocco JM, Jones AP. Organizational conditions affecting withdrawal intentions and decisions as moderated by work experience. Psychol Rep. 1980;46(3):1223-31. Doi:10.2466/pr0.1980.46.3c.1223

- Quadagno JS. Book Review: Price JL. The Study of Turnover. University of Iowa Press, Ames, Iowa. c1977. Sociol Work Occup. 1978;5(4):487-9. Doi:10.1177/073088847800500406.

- Porter, LW, Steers RM. Organization, work, and personal factors in employee turnover and absenteeism. Psychol. Bull. 1973;80(2):151-76. Doi:10.1037/h0034829.

- Porter LW, Steers RM, Mowday RT, Boulian PV. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J Appl Psychol. 1974;59(5):603-9. Doi:10.1037/h0037335.

- Marsh RM, Mannari H. Organizational commitment and turnover: A Prediction Study. Adm Sci Q. 1977 Mar;22(1):57-75. Doi:10.2307/2391746

- Kovner CT, Brewer CS, Fatehi F, Jun J. What does nurse turnover rate mean and what is the rate? Policy Polit Nurs. Pract. 2014 Aug-Nov;15 (3-4):64-71. Doi:10.1177/1527154414547953.

- Coomber B, Barriball KL. Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: A Review of the Research Literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007 Feb;44(2):297-314. Doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.004.

- Brewer CS, Chao Y-Y, Colder CR, Kovner CT, Chacko TP. A structural equation model of turnover for a longitudinal survey among early career registered nurses. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015 Nov;52(11):1735-45. Doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.06.017.

- Dexter F, Epstein R, Elhakim M, O’Sullivan C. US Survey of incidence of and reasons for nurse anesthetists leaving or having considered leaving their jobs. AANA J. 2021 Dec;89(6):484-90.

- Steil AV, Alves S. Antecedents of intention to leave the organization: A Systematic Review Antecedentes Da Intenção de Sair Da Organização: Uma Revisão Sistemática Los Antecedentes de La Intención de Salir de La Organización: Una Revisión Sistemática. 2019;29:1-11.

- Karaferis D, Aletras V, Niakas D. Job satisfaction and associated factors in greek public hospitals. Acta Biomed [Internet]. 2022 Oct; 93(5):e2022230. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36300228/ Doi:10.23750/abm.v93i5.13095.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983 Dec;24(4):385-96.

- Haslam D, Filus A, Morawska A, Sanders MR, Fletcher R. The work-family conflict scale (WAFCS): Development and initial validation of a self-report measure of work-family conflict for use with parents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2014;46:346-57. Doi:10.1007/s10578-014-0476-0.

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A Cross-National Study. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006 Aug;66(4):701-16. Doi:10.1177/0013164405282471.

- Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manag J. 1995;38(5):1442-65. Doi:10.2307/256865.

- Mowday RT, Steers RM, Porter LW. The measurement of organizational commitment. 1979 Apr;14(2):224-47.

- Hill KS. Work satisfaction, intent to stay, desires of nurses, and financial knowledge among bedside and advanced practice nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2011 May;41(5):211-7. Doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182171b17.

- Sibuea ZM, Sulastiana M, Fitriana E. Factor affecting the quality of work life among nurses: A Systematic Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024 Feb:17:491-503. Doi:10.2147/JMDH.S446459.

- Lee E-K, Kim J-S. Nursing stress factors affecting turnover intention among hospital nurses. Int J Nurs Pract [Internet]. 2020 Dec;26(6):e12819. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31997511/ Doi:10.1111/ijn.12819.

- Yu F, Chu G, Yeh T, Fernandez, R. Effects of interventions to promote resilience in nurses: A Systematic Review. Int J Nurs Stud [Internet]. 2024 Sep;157:104825. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104825. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38901125/

- Ouyang Y-Q, Zhou W-B, Qu H. The impact of psychological empowerment and organisational commitment on chinese nurses’ job satisfaction. Contemp Nurse. 2015;50 (1):80-91. Doi:10.1080/10376178.2015.1010253.

- Oyeleye O, Hanson P, O’Connor N, Dunn D. Relationship of workplace incivility, stress, and burnout on nurses’ turnover intentions and psychological empowerment. J Nurs Adm. 2013 Oct;43(10):536-42. Doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182a3e8c9.

- Fragkos KC, Makrykosta P, Frangos CC. Structural empowerment is a strong predictor of organizational commitment in nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2020 Apr;76(4):939-62. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14289.

- Ibrahem SZ, Elhoseeny T, Mahmoud RA. Workplace empowerment and organizational commitment among nurses working at the main University Hospital, Alexandria, Egypt J Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2013 Aug;88(2):90-6.

- Cho J, Laschinger HKS, Wong C. Workplace empowerment, work engagement and organizational commitment of new graduate nurses. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2006 Sep;19(3):43-60. Doi:10.12927/cjnl.2006.18368.

- Ko J-W, Price JL, Mueller CW. Assessment of meyer and allen’s three-component model of organizational commitment in south korea. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82(6):961-73.

- San Park J, Hyun Kim, T. Do Types of Organizational Culture Matter in Nurse Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention? Leadersh. Heal. Serv. 2009 Feb;22:20-38. Doi:10.1108/17511870910928001.

- Medicine C, Symeonidis S, Anestiadou E, Bitsianis S, Gemousakakis G, Ntampakis G, et al. Abdominal wall defect reconstruction with use of biological mesh and negative pressure wound therapy: A Case Report. Maedica (Bucur). 2022 Jun;17(2):518-23.

- Atkins PM, Marshall BS, Javalgi RG. Happy employees lead to loyal patients. Survey of nurses and patients shows a strong link between employee satisfaction and patient loyalty. J Health Care Mark. 1996 Winter;16(4):14-23. PMID: 10169075.

- Maleki R, Janatolmakan M, Fallahi M, Andayeshgar B, Khatony A. Intention to leave the profession and related factors in nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study in Kermanshah. Iran Nurs open. 2023 Jul;10(7):4298-304. Doi:10.1002/nop2.1670.

- Hanum AL, Hu Q, Wei W, Zhou H, Ma F. Professional Identity, Job Satisfaction, and Intention to Stay among Clinical Nurses during the Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mediation Analysis. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2023 Apr;20(2):e12515. Doi:10.1111/jjns.12515.

- Tourangeau A, Saari M, Patterson E, Ferron EM, Thomson H, Widger, K.; MacMillan, K. Work, Work Environments and Other Factors Influencing Nurse Faculty Intention to Remain Employed: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurse Educ Today. 2014 Jun;34(6):940-7. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.10.010.

- Shields M, Ward M. Improving nurse retention in the british national health service: The impact of job satisfaction on intentions to quit. SSRN Electron J [Internet]. 2000 May. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=224216 Doi:10.2139/ssrn.224216.