Case Report

Hell J Surg. 2024 Oct-Dec;94(4):227–233

doi: 10.59869/24051

Orestis Ioannidis, Ourania Kerasidou, Elissavet Anestiadou, Aikaterini-Antonia Bourtzinakou, Aliki Brenta, Eleni Salta-Poupnara, Freiderikos Tserkezidis, Magdalini Kaprianou, Evangelia Ioannidou, Savvas Symeonidis, Stefanos Bitsianis, Efstathios Kotidis, Stamatios Angelopoulos

Fourth Department of Surgery, “George Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Exochi, Greece

Correspondence: Elissavet Anestiadou, MD, MSc, PhDc, Fourth Department of Surgery, General Hospital “George Papanikolaou”, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Exochi, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece, e-mail: elissavetxatz@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Open abdomen (OA) is indicated in numerous medical settings, such as trauma, abdominal sepsis, severe acute pancreatitis, and intra-abdominal hypertension. Managing an open abdomen presents a complex and challenging scenario for surgeons, requiring specialised techniques and comprehensive decision-making to prevent complications, especially in obese patients, due to increased morbidity and mortality rates. Herein we describe the use of vertical mesh-mediated fascial traction (VMMFT) in combination with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) to prevent fascial retraction and manage OA in a super-super obese patient who developed abdominal compartment syndrome following a massive abdominal ventral hernia repair. A 55-year-old male with a BMI of 62 kg/m2 underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy for a massive ventral hernia with bowel strangulation. Postoperatively, he developed abdominal compartment syndrome, necessitating relaparotomy and temporary abdominal closure. A traction device was introduced to facilitate vertical mesh-mediated fascial traction (VMMFT). On postoperative day six, fascial closure was achieved without complications. This case highlights the efficacy of VMMFT combined with NPWT in preventing fascial retraction, promoting abdominal wall expansion, and reducing the need for complex reconstructions. Further studies are warranted to assess its broader clinical and economic impact.

Key Words: Obesity, open abdomen, abdominal compartment syndrome, vertical mesh-mediated fascial traction, negative pressure wound therapy, fascial closure, abdominal wall reconstruction

Submission: 08.02.2025, Acceptance: 29.04.2025

INTRODUCTION

Open abdomen (OA) is a complex, life-saving yet challenging strategy, characterised by the intentional decision to leave the fascial edges unapproximated after laparotomy or by actively opening the abdomen to prevent abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) [1]. OA serves as an essential surgical strategy, particularly in the management of ongoing sepsis, haemorrhage control, or decompression of intra-abdominal hypertension. In both trauma and non-trauma scenarios, OA has demonstrated efficacy in mitigating severe physiological disturbances when alternative therapeutic measures prove inadequate [2]. However, prolonged OA is associated with substantial risks, including excessive fluid loss, infectious complications, and loss of domain, all of which hinder definitive closure. Given the potential exposure of the abdominal contents, temporary abdominal closure (TAC) is essential to protect the viscera and mitigate complications [3].

Early primary fascial closure is critical to prevent complications such as enteroatmospheric fistula formation, minimize wound infections, and reduce the physiological stress associated with prolonged open abdomen management. Moreover, prompt closure facilitates early mobilization, decreases the risk of long-term complications such as ventral hernia recurrence, and can significantly reduce hospital stay and overall treatment costs, particularly in obese patients with limited physiological reserve [4]. Timely closure also helps to restore abdominal wall integrity and function, preserving respiratory mechanics and improving overall patient comfort, which is especially crucial in critically ill patients who are vulnerable to respiratory compromise. Additionally, achieving early fascial closure reduces the burden of prolonged intensive care, limits fluid and protein loss, and decreases the need for complex reconstructive procedures, ultimately contributing to better long-term functional outcomes and quality of life [3].

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for heightened morbidity and mortality among critically ill patients [5]. In particular, in cases of open abdomen management, obesity compounds these risks due to elevated intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), impaired wound healing, and technical challenges associated with abdominal closure and fascial re-approximation [6]. Consequently, the management of OA in this patient population requires tailored strategies to optimize outcomes and minimize adverse effects.

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is widely utilised in the management of OA, offering several advantages, including visceral protection, reduced adhesion formation, active drainage of exudative and infectious fluid, and preservation of the abdominal domain [7]. When combined with a visceral protection layer, NPWT also reduces the risk of enteroatmosphaeric fistula (EAF) formation and can be used for their management [8]. Furthermore, NPWT facilitates progressive fascial approximation, thereby reducing the necessity for complex reconstructive interventions and improving overall patient outcomes.

Mesh-mediated fascial traction (MMFT) has been a well-established method to promote progressive closure of the open abdomen by suturing the fascia to an interposed mesh, which is gradually tightened over time [9]. While effective, MMFT requires multiple returns to the operating room for mesh retightening, is associated with longer ICU stays, and may be influenced by variable fluid management strategies [10]. Vertical mesh-mediated fascial traction (VMMFT) evolved from MMFT to enhance the likelihood of successful fascial closure. It also addresses these limitations by enabling continuous traction, reducing the need for multiple reoperations, and providing more predictable fascial approximation dynamics.

Vertical mesh-mediated fascial traction (VMMFT) applies dynamic traction to the abdominal wall through vertically and anteriorly directed forces. In this case, the technique was implemented using a dedicated traction device designed for continuous application of controlled tension [11]. This method applies vertical and anteriorly directed traction to counteract fascial retraction while concurrently permitting intra-abdominal volume expansion. The integration of VMMFT with NPWT has yielded favorable outcomes in achieving early definitive closure, by mitigating the challenges associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure and delayed fascial approximation. However, literature data regarding the combined application of VMMFT and NPWT in obese patients are still scarce.

This case report details the successful application of VMMFT and NPWT in a critically ill, super-super obese patient with OA following an emergency laparotomy, underscoring the critical role of early fascial closure strategies in the comprehensive management of complex abdominal wall defects. It is presented in accordance with the Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines [12]. The patient was fully informed, and written informed consent for the publication of this case report and accompanying images was obtained. Copies of the written consent are available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

CASE REPORT

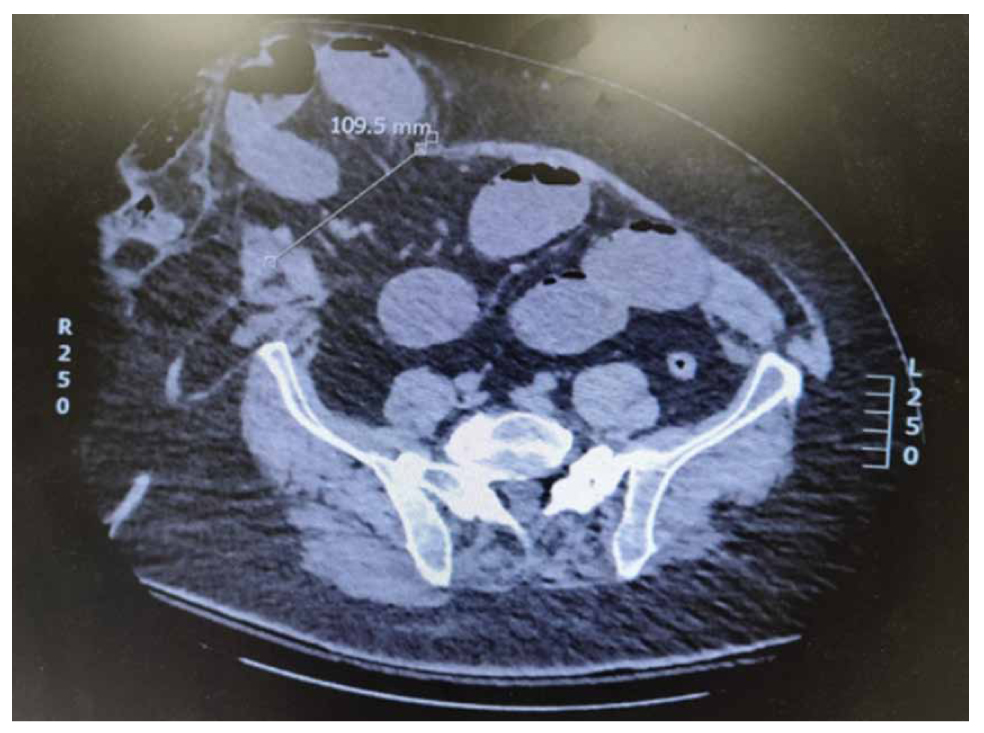

A 55-year-old super-super obese male with a BMI of 62 kg/m² presented to the emergency department with five days of abdominal pain and vomiting of intestinal contents. Upon presentation, he was haemodynamically unstable, with a systolic blood pressure of 85mmHg and 130 bpm. The patient had no history of prior abdominal surgeries. Clinical examination revealed a distended abdomen with tympanicity, hyperactive bowel sounds, tenderness, and rebound tenderness. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). Imaging findings included an upright abdominal X-ray showing air-fluid levels in small and large intestines and a CT scan identifying a large midline and right lateral abdominal wall hernia containing small and large bowel, including the ileocecal valve (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preoperative CT scan showing a large midline and right lateral abdominal wall hernia containing small and large bowel, including the ileocecal valve.

The patient underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy, which revealed a massive abdominal wall hernia defect measuring 110 mm. The significant size of the hernia and the presence of bowel strangulation necessitated urgent surgical intervention to prevent irreversible ischemic damage and to restore intestinal continuity. An open right hemicolectomy with side-to-side anastomosis was performed, and a a biologically derived, fully resorbable knitted monofilament mesh scaffold using Poly-4-hydroxybutyrate (P4HB) was placed intraperitoneally, with primary closure of the abdominal wall. Given the significant hernia defect and concern for high-tension primary closure in a super-super obese patient, an intraperitoneal mesh was initially placed to reinforce the abdominal wall and mitigate the risk of early postoperative dehiscence. In the context of emergency surgery, the intraperitoneal position allowed rapid reinforcement without the need for extensive dissection of retromuscular or preperitoneal planes, which would have prolonged operative time and increased the risk of bleeding in this critically ill, high-BMI patient. In emergency settings, especially when time is critical and contamination is borderline or uncertain, intraperitoneal mesh is often preferred for its ability to provide swift and effective reinforcement at the peritoneal level when posterior or preperitoneal planes are not safely accessible. Sublay positioning would have required time-intensive retromuscular dissection, with increased bleeding risk in an obese patient. Similarly, an onlay mesh was avoided due to the heightened risk of seroma formation and superficial infection in high-BMI individuals. The patient was admitted to the ICU postoperatively.

On postoperative day one, the patient developed fever (39°C), oliguria, and elevated intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) of 20 mmHg. While fever is not typically associated with the initial onset of abdominal compartment syndrome, in this case, it likely reflected a systemic inflammatory response following bowel ischemia and emergency enterectomy. The combination of escalating IAP and organ dysfunction led to the diagnosis of postoperative ACS. An urgent relaparotomy was performed, during which the intraperitoneal mesh was removed. The anastomosis was intact, but abdominal closure was not feasible. Instead, the abdomen was left open using NPWT with intra-abdominal vacuum-assisted closure (VAC). An intraperitoneal composite mesh was placed inlay to prevent fascial retraction, using the bridging technique. The initial fascial separation was 19 cm under full muscle relaxation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Intraoperative view after urgent relaparotomy, demonstrating an open abdomen with NPWT applied and Prolene mesh placement to prevent fascial retraction.

Initial use of NPWT at -125 mmHg alone did not halt fascial retraction. The therapeutic breakthrough was achieved after combining NPWT with VMMFT, suggesting that while NPWT facilitated fluid evacuation and domain preservation, dynamic traction was essential to counteract fascial retraction.

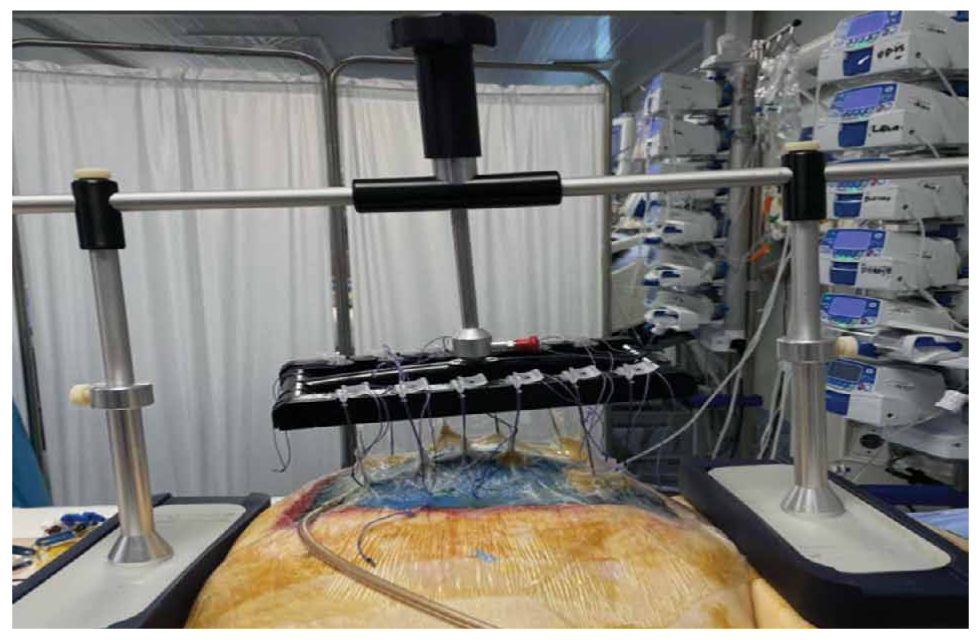

On postoperative day three, due to worsening fascial retraction, the technique of vertical mesh-mediated fascial traction (VMMFT) was initiated. The posterior fascial mesh was carefully incised to adjust the position of the traction interface, and the tension sutures were placed through the mesh material itself rather than directly in the anterior fascia, in accordance with the standard VMMFT technique, using six sutures to distribute the applied force evenly. Therapy sessions lasted three hours, with one-hour breaks, paused overnight with sutures under mild tension. Tension settings were continuously monitored using a color scale and adjusted as needed. A photograph illustrating the application of the traction device during therapy sessions has been included to aid in visualising the method used (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Application of the traction device during VMMFT therapy sessions. The anterior fascial edges are secured to the traction device using multiple sutures, with dynamic traction applied according to manufacturer recommendations. This image illustrates the setup during active therapy, although no image is available of the provisional overnight closure with sutures under mild tension.

On postoperative day 6 of VMMFT, intraoperative assessment showed a significant reduction in fascial distance, with no macroscopic signs of fascial necrosis or damage, allowing successful primary fascial closure of the abdominal wall, using a biologically derived, fully resorbable knitted monofilament mesh scaffold made of Poly-4-hydroxybutyrate (P4HB) in an onlay fashion. Importantly, primary fascial closure (PFC) was successfully achieved on postoperative day six, marking the major outcome of this case and underscoring the efficacy of combined VMMFT and NPWT therapy. Given the achievement of complete fascial approximation without undue tension, and considering the previously contaminated nature of the open abdomen, we consciously opted against placing a sublay mesh during definitive closure. Implanting prosthetic material in this context carries a well-recognised risk of surgical site infection, mesh colonisation, and possible explantation, which could jeopardise the success of reconstruction. Furthermore, avoiding retromuscular dissection and sublay mesh placement allowed us to preserve the anatomical planes for potential future reconstructive procedures, maintaining flexibility in case of long-term complications or hernia recurrence.

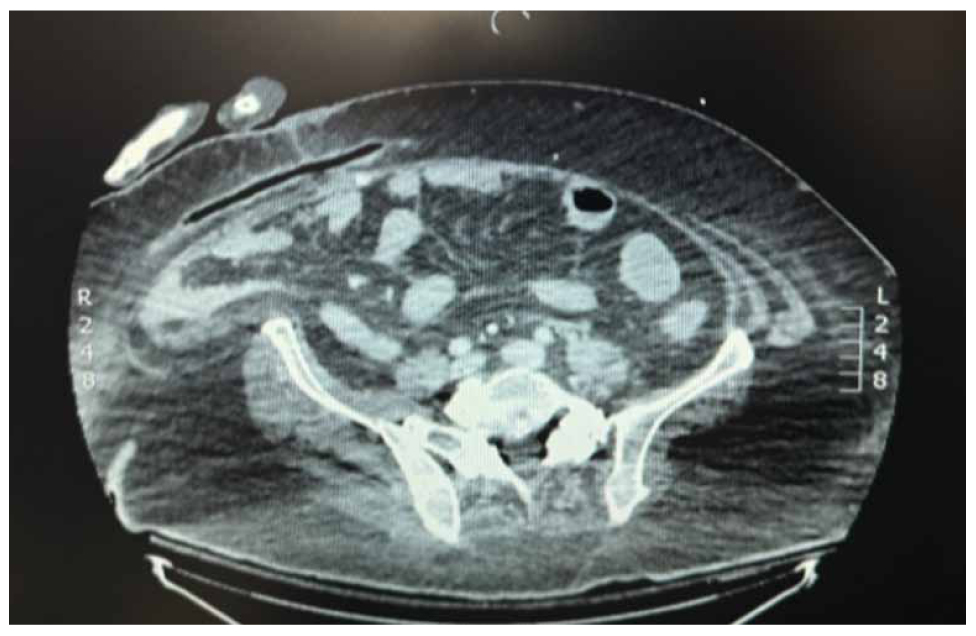

Postoperatively, the patient remained haemodynamically stable, and no device-related complications were reported. Postoperative imaging provided further confirmation of successful surgical outcomes. A CT scan performed approximately five days after definitive fascial closure and Phasix™ onlay mesh placement, as part of the diagnostic workup for postoperative fever, demonstrated effective midline fascial approximation and convergence of the linea alba. These findings corroborated the intraoperative assessment of a tension-free closure and reinforced the efficacy of the combined approach of NPWT and dynamic fascial traction in restoring abdominal wall integrity (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Postoperative CT scan performed approximately five days after definitive fascial closure and Phasix™ onlay mesh placement, in the context of fever investigation. The image demonstrates successful midline fascial approximation with convergence of the linea alba, supporting the effectiveness of the chosen closure strategy.

The successful management of this complex case was the result of close collaboration within a multidisciplinary team, comprising surgeons, anesthesiologists, intensivists, ICU physicians, nutritionists, and specialised nursing staff. Daily team discussions allowed for coordinated care, including adjustment of fluid management, nutritional support, and mobilization strategies, all of which contributed to achieving early primary fascial closure and an overall favorable outcome.

DISCUSSION

As emphasised earlier, early primary fascial closure plays a pivotal role in improving outcomes for patients with an open abdomen, especially in obese individuals who face heightened risks. Managing OA in obese patients is challenging due to elevated IAP, impaired wound healing, and increased risk of complications. In addition, reconstructing the abdominal wall following an OA remains a significant surgical challenge [13]. The combination of NPWT with vertical mesh-mediated fascial traction (VMMFT) effectively prevented fascial retraction, reduced long-term complications, expanded the abdominal domain, alleviated the effects of abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS), and facilitated early definitive closure, minimising the need for extensive reconstruction [14–17]. By combining NPWT with VMMFT, an evolution of the established MMFT technique that offers significant advantages, fascial retraction was effectively prevented and early definitive closure was facilitated. Compared to MMFT, which typically requires repeated surgical interventions for mesh tightening and is influenced by factors such as fluid shifts and patient positioning, VMMFT provides continuous, controlled traction, allowing progressive fascial approximation without the need for repeated operations [18]. This advancement reduces ICU stay, minimizes the burden of multiple anesthetic procedures, and optimizes the conditions for early closure, especially in critically ill or obese patients. In addition, we elected not to place a sublay mesh during final closure to reduce the risk of infection in this previously contaminated field, as primary fascial closure was achieved without tension.

Alternative closure strategies, including anterior or posterior component separation techniques such as transversus abdominis release (TAR), were considered as potential options for definitive closure. However, given the progressive and satisfactory reduction in fascial separation achieved through the combined use of dynamic traction and NPWT, primary closure was successfully accomplished without the need for additional dissection. Proceeding with component separation in this setting would have entailed extensive tissue mobilization and prolonged operative time, increasing the risks of wound morbidity, seroma formation, and infectious complications, particularly in a super-super obese patient with a previously contaminated surgical field [19]. By avoiding further dissection and favoring a less invasive closure strategy, we prioritised minimising operative trauma while promoting early recovery and reducing the potential for postoperative complications [20].

A recent case series study of nine patients with OA and risk for ACS reported a 76% reduction in fascia-to-fascia distance using NPWT combined with VMMFT, with an associated decrease in IAP from 31 mmHg to 8.5 mmHg. Three patients died before achieving definitive fascial closure (DFC), while the remaining six successfully underwent DFC [16]. Another retrospective study by Mones et al. documented a mean closure time of 6.2 days with VMMFT in heterogeneous OA patients. Our case aligns with these findings, further supporting the safety and efficacy of this approach in super-super obese patients [11].

Beyond technical success, an important consideration in the management of OA in obese patients is the impact on postoperative recovery and long-term functional outcomes. Early closure of the abdominal wall reduces the incidence of enteroatmospheric fistulas, minimizes the risk of wound infections, and facilitates early mobilization, which is particularly crucial in obese patients with limited physiological reserve [21]. Additionally, effective closure strategies decrease the likelihood of ventral hernia recurrence, which is a common long-term complication in this patient population. From a healthcare perspective, achieving early fascial closure can significantly reduce hospital length of stay, decrease the need for prolonged intensive care, and lower overall treatment costs [22]. The use of VMMFT combined with NPWT may offer a cost-effective solution by decreasing the duration of hospitalization, reducing reoperation rates, and limiting the necessity for long-term wound care management [23]. However, additional prospective studies are necessary to quantify these economic benefits in a broader cohort.

Another area requiring further investigation is the impact of patient selection criteria on outcomes. While our case demonstrates successful closure in a super-super obese patient, future research should explore the role of frailty scores, preoperative nutritional optimization, and individualised treatment protocols in predicting which patients will derive the most benefit from this approach. In addition, long-term follow-up is essential to determine the durability of the closure and the incidence of late complications such as hernia recurrence and abdominal wall weakness.. Overall, this case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the management of OA in obese patients, involving collaboration between surgeons, anesthesiologists, intensivists, ICU physicians, nutritionists, and specialised nursing staff to optimize perioperative care and improve patient outcomes. In this case, regular multidisciplinary team briefings enabled coordinated decision-making, effective fluid management, tailored nutritional support, and mobilization strategies, all of which were crucial to achieving a successful outcome.

While we were able to include an image illustrating the application of the traction device during therapy, we acknowledge the absence of photographic documentation of the provisional overnight closure with sutures under mild tension as a limitation of this report. Future cases should aim to include comprehensive imaging at all stages of therapy to enhance reproducibility and optimize understanding of the technique.

CONCLUSION

Dynamic vertical traction, when combined with NPWT, effectively prevented fascial retraction, expanded the abdominal domain, and facilitated early primary fascial closure. This approach may reduce the need for complex reconstruction, decrease reliance on synthetic meshes, and improve overall patient outcomes. Future studies should evaluate its broader clinical applicability and economic impact, with a focus on patient selection, long-term functional outcomes, and healthcare cost-effectiveness. Importantly, this case also highlights the critical role of a coordinated multidisciplinary team in achieving successful early closure and optimising outcomes in high-risk, super-obese patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Coccolini F, Roberts D, Ansaloni L, Ivatury R, Gamberini E, Kluger Y, et al. The open abdomen in trauma and non-trauma patients: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg [Internet]. 2018 Feb;13:7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29434652/

- Chabot E, Nirula R. Open abdomen critical care management principles: Resuscitation, fluid balance, nutrition, and ventilator management. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open [Internet]. 2017 Sep;2(1):e000063 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29766080/

- Heo Y, Kim DH. The temporary abdominal closure techniques used for trauma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2023 Apr;104(4):237–47.

- Chen Y, Ye J, Song W, Chen J, Yuan Y, Ren J. Comparison of outcomes between early fascial closure and delayed abdominal closure in patients with open abdomen: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract [Internet]. 2014;2014:784056. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24987411/

- Duchesne JC, Schmieg REJ, Simmons JD, Islam T, McGinness CL, McSwain NEJ. Impact of obesity in damage control laparotomy patients. J Trauma. 2009 Jul;67(1):108-12.

- Yetisir F, Salman AE, Acar HZ, Özer M, Aygar M, Osmanoglu G. Management of septic open abdomen in a morbid obese patient with enteroatmospheric fistula by using standard abdominal negative pressure therapy in conjunction with intrarectal one. Case Rep Surg [Internet]. 2015;2015:293946. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26779360/

- Navsaria P, Nicol A, Hudson D, Cockwill J, Smith J. Negative pressure wound therapy management of the “open abdomen” following trauma: A prospective study and systematic review. World J Emerg Surg [Internet]. 2013 Jan;8(1):4. Available from: https://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1749-7922-8-4

- Bobkiewicz A, Walczak D, Smoliński S, Kasprzyk T, Studniarek A, Borejsza-Wysocki M, et al. Management of enteroatmospheric fistula with negative pressure wound therapy in open abdomen treatment: A multicentre observational study. Int Wound J. 2017 Feb;14(1):255–64.

- Taylor D, Dooreemeah D, Al-Habbal Y, Jacobs R. Vacuum assisted closure with mesh mediated fascial traction of open abdominal wounds and acute fascial dehiscence, a single institution experience. ANZ J Surg. 2023;93(7–8):1793–8.

- Shakya S, Tamrakar A, Pangeni A, Shrestha AK, Basu S. EP202 – Mesh-Mediated Fascial Traction (MMFT) and Negative Pressure Abdominal Dressing (ABTHERA): Useful in difficult open abdomens? Br J Surg [Internet]. 2024 Sep;111(Supplement_8):znae197.457. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znae197.457

- Mones T, Chobanova V, Halama T, Nowroth T, Pronadl M. Vertical Mesh-Mediated fascial traction and negative pressure wound therapy: A Case series of nine patients in general and vascular surgery. Surg Technol Int. 2024 Jul;44:131–7.

- Agha RA, Fowler AJ, Saeta A, Barai I, Rajmohan S, Orgill DP, et al. The SCARE Statement: Consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int J Surg. 2016;34:180–6.

- Bruhin A, Ferreira F, Chariker M, Smith J, Runkel N. Systematic review and evidence based recommendations for the use of negative pressure wound therapy in the open abdomen. Int J Surg. 2014 Oct;12(10):1105–14.

- Eickhoff R, Guschlbauer M, Maul AC, Klink CD, Neumann UP, Engel M, et al. A new device to prevent fascial retraction in the open abdomen – proof of concept in vivo. BMC Surgery [Internet]. 2019 Jul;82 Available from: https://bmcsurg.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12893-019-0543-3

- Fung S, Ashmawy H, Krieglstein C, Halama T, Schilawa D, Fuckert O, et al. Vertical traction device prevents abdominal wall retraction and facilitates early primary fascial closure of septic and non-septic open abdomen. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2022 Aug;407(5):2075–83.

- Dohmen J, Weissinger D, Peter AST, Theodorou A, Kalff JC, Stoffels B, et al. Evaluating a novel vertical traction device for early closure in open abdomen management: A consecutive case series Front Surg. 2024 Aug:11:1449702 Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2024.1449702

- Hofmann AT, Gruber-Blum S, Lechner M, Petter-Puchner A, Glaser K, Fortelny R. Delayed closure of open abdomen in septic patients treated with negative pressure wound therapy and dynamic fascial suture: the long-term follow-up study. Surg Endosc. 2017 Nov;31(11):4717–24.

- Pillay P, Smith MTD, Bruce JL, Clarke DL, Bekker W. The Efficacy of VAMMFT compared to “Bogota Bag” in achieving sheath closure following temporary abdominal closure at index laparotomy for trauma. World J Surg. 2023 Jun;47(6):1436–41.

- Riediger H, Köckerling F. Limitations of Transversus Abdominis Release (TAR)-Additional Bridging of the Posterior Layer And/Or Anterior Fascia Is the Preferred Solution in Our Clinical Routine If Primary Closure is Not Possible. J Abdom wall Surg JAWS [Internet]. 2024 Jun;3:12780. Available from: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/journals/journal-of-abdominal-wall-surgery/articles/10.3389/jaws.2024.12780/full

- López-Cano M, García-Alamino JM, Antoniou SA, Bennet D, Dietz UA, Ferreira F, et al. EHS clinical guidelines on the management of the abdominal wall in the context of the open or burst abdomen. Hernia. 2018 Dec;22(6):921–39.

- Scott BG, Feanny MA, Hirshberg A. Early definitive closure of the open abdomen: A Quiet Revolution. Scand J Surg. 2005;94(1):9-14.

- Hees A, Willeke F. Case Report Prevention of Fascial Retraction in the Open Abdomen with a Novel Device. Case Rep Surg. 2020 Oct:2020:8254804.

- Willms A, Schaaf S, Schwab R, Richardsen I, Bieler D, Wagner B, et al. Abdominal wall integrity after open abdomen: Long-term results of vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction (VAWCM). Hernia. 2016 Dec;20(6):849–58.